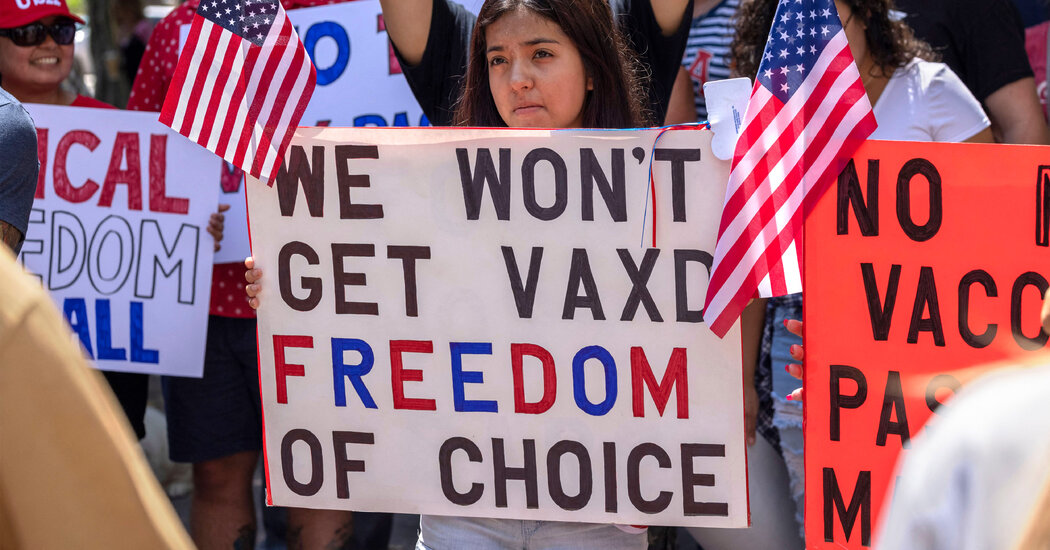

Renée DiResta, a researcher at Stanford, found through Twitter analysis that there was “an evolution in messaging.” The movement discovered that a focus on freedom “was more resonant with legislators and would help them actually achieve their political goals,” Ms. DiResta said to me. Anti-vaccine Twitter accounts that had been posting for years about autism and toxins pivoted to Tea Party-esque ideas, leading to the emergence of a new cluster of accounts focused on “vaccine choice” messaging, Ms. DiResta said.

Anti-vaccine activists used the measles outbreak and others to claim public officials would force “harmful” vaccines on people. They also found new ways to court politicians, especially those who take pride in bucking the system.

Just a week after the California bill had been filed, a well-meaning Republican legislator in Texas, Jason Villalba, filed a similar bill in Austin. But Mr. Villalba didn’t realize that anti-vaccine sentiment had been growing in his state, and his bill unwittingly “kicked the hornet’s nest,” said Rekha Lakshmanan, the director of advocacy and public policy for a Texas-based nonprofit group, the Immunization Partnership. “All of a sudden we saw a kind of new generation of the anti-vaccine movement in Texas emerge.”

Though Mr. Villalba’s bill never got to a vote, it helped drive the new guard to form Texans for Vaccine Choice, which would become a PAC, to lobby against the legislation. Other influential conservative state PACs took notice and may have joined forces with Texans for Vaccine Choice behind the scenes. The group’s emphasis on parents’ rights and medical freedom was a natural fit, aligning them with Tea Party-type Republicans like Jonathan Stickland, whose ringing cry for any issue was “freedom.”

Likely under the tutelage of conservative grass-roots groups, the fledgling anti-vaccine PAC learned effective political electioneering. It backed a champion for its cause to challenge Mr. Villalba in the Republican primary, a far-right politician named Lisa Luby Ryan. When Ms. Ryan defeated Mr. Villalba, Texans for Vaccine Choice cried victory. That Ms. Ryan eventually lost the general election was beside the point. Anti-vaccine activists had shown they were a formidable force, and Texas Republicans learned it was “politically expedient” to stay silent when, for example, Mr. Stickland attacked vaccine scientists, as The Houston Chronicle editorial board wrote.

With vaccine refusal reframed as “parent choice,” Republicans could no longer risk appearing to oppose “freedom of choice” on any issue. More state anti-vaccine PACs and nonprofit groups formed, and social media allowed greater collaboration. The “freedom” messaging united anti-vaccine groups, particularly those in Texas and California, and withstood social media platforms’ growing attempts to stanch false claims.

New anti-vaccine organizations also began fund-raising in earnest, bringing in millions of dollars, both from wealthy donors and by selling fear. They use this money to create slick propaganda for larger audiences, such as a spate of anti-vaccine films like “Vaxxed,” which provided a blueprint for pandemic denialism films like “Plandemic.” And they donate funds to the politicians they hope to win over.