LAS VEGAS — Maurice Clark huddled in his tent alongside dusty railroad tracks as two homeless-outreach employees started asking him questions to find out whether or not he would qualify without spending a dime or backed housing.

Did he use medicine? Had he ever been in jail? What number of instances had he been to an emergency room? Had he been attacked on the streets? Tried to hurt himself? Engaged in intercourse for cash?

Clark didn’t really feel snug being sincere with the 2 surveyors he’d by no means met earlier than, who have been flanked by law enforcement officials as they recorded his responses from a questionnaire on a pill.

“I’ve done some crazy things to survive, but I’m, like, I’m going to say no because there’s these officers right there,” he mentioned, recalling the encounter on a fall afternoon outdoors his tent.

“I’m a Black man in America, so asking this stuff hits a little bit different.”

Nationwide homelessness specialists and native leaders say such private questions exacerbate racial disparities within the ranks of the nation’s unhoused, notably as extra individuals experiencing homelessness compete for scarce taxpayer-subsidized housing amid a deepening affordability disaster.

Vulnerability questionnaires have been created to find out how possible an individual is to get sick and die whereas homeless, and the system has been adopted broadly across the nation over the previous decade to assist prioritize who will get housing. The extra a homeless particular person is perceived to be weak, the extra factors they rating on the questionnaire and the upper they transfer within the housing queue. The surveys are being singled out for worsening racial disparities by systematically inserting homeless white individuals on the entrance of the road, forward of their Black friends — partly as a result of the scoring awards extra factors for utilizing well being care, and depends on belief within the system, each of which favor white individuals.

Black individuals make up 13.7% of the general U.S. inhabitants but account for 32.2% of the nation’s homeless inhabitants. White individuals, together with some individuals of Hispanic descent, make up 75% of the nation and characterize 55% of America’s homeless.

“It’s racist in a systemic way,” mentioned Marc Dones, a California-based coverage director on the College of California-San Francisco and a lead researcher for one of many nation’s largest research analyzing the Black homeless inhabitants. “If you’re a white person, the more likely you are to rank higher than if you’re a Black person, so you’re more likely to get selected for housing.”

Vulnerability surveys took off after President Barack Obama in 2009 signed into regulation sweeping guidelines requiring the nation’s native homelessness companies, often called Continuums of Care and at the moment numbering 381, to undertake a way to evaluate the vulnerability of homeless individuals to obtain federal housing and homelessness funding. Cities and counties predominantly adopted a survey referred to as VI-SPDAT, which continues to be utilized by an estimated two-thirds of homeless companies, even because it has been discovered to favor white individuals and rank Black individuals decrease.

Some specialists argue it’s time to toss the vulnerability evaluation altogether and look not solely at well being and social wants but additionally systemic racism, poverty, involvement within the felony justice system, limitations to housing, and different financial drivers that affect, and in some instances trigger, homelessness. A number of U.S. communities are revamping their vulnerability evaluation programs to scale back racial disparities and assist extra Black individuals get housing.

In Los Angeles, officers are launching an effort to make use of synthetic intelligence to higher assess whether or not somebody needs to be prioritized for placement, partly by taking a look at overpolicing of Black individuals and discrimination in well being care. In Las Vegas, officers are revamping their vulnerability evaluation to present greater scores for systemic issues together with incarceration. In Austin, Texas, officers are testing a system to account for individuals displaced by gentrification.

“We need to own the racism that is embedded in our systems,” mentioned Quiana Fisher, vice chairman of homelessness response programs for the lead company in Travis County, Texas, which incorporates Austin. “It’s not just about the tool — it’s about funding, and it’s about program outcomes. Even if it’s unintentional, we have created a homeless response system that is rooted in racism.”

The evaluation device was first examined in Boston, the place members of the homeless inhabitants have been extra prone to be white, male, and have a extreme psychological sickness or substance use dysfunction. Black individuals, in the meantime, usually tend to be homeless due to financial causes, equivalent to poverty or joblessness, and are much less prone to have a report of medical care as a result of greater uninsurance and fewer use of well being care.

“This whole system was piloted on this older white population in Boston, so it does a poor job of capturing the needs of Black folks, who don’t tend to be as sick as white folks — they’re more broke,” Dones mentioned. “The initial thought was to prioritize these people because they’re going to die sooner. It was trying to tackle mortality, but it wound up in racism.”

Consequently, white persons are extra prone to acquire housing as a result of they have an inclination to attain extra factors on vulnerability assessments that rank illness greater, together with histories of continual illness, habit, psychological sickness, and emergency room visits and hospitalizations, in line with nationwide surveys. Black individuals, in the meantime, are much less prone to have medical health insurance or medical diagnoses and to disclose their illnesses, and are extra mistrustful as a result of biases within the well being care system. “Black folks are less likely to seek care, even with coverage, due to medical racism,” Dones mentioned.

Native leaders say a part of the issue is turning into homeless within the first place and financial disadvantages that drive extra Black individuals into homelessness, together with placement in foster care and better charges of eviction and joblessness. However as soon as homeless, serving to Black individuals get into steady housing turns into extra elusive.

In Los Angeles County, dwelling to extra homeless individuals than another county within the nation, 31% of homeless persons are Black, although the general Black inhabitants accounts for 9%. In Austin, Black individuals account for practically 32% of the homeless inhabitants, in contrast with 7.6% total. And in Clark County, which incorporates Las Vegas, Black individuals characterize 42% of the homeless inhabitants however simply 12% of the general inhabitants.

“We’ve failed to capture the complex vulnerabilities of our marginalized groups. We’re asking all these questions, but we created a waiting list to nowhere,” mentioned Brenda Barnes, who leads the Southern Nevada Homelessness Continuum of Care.

Streets of Las Vegas

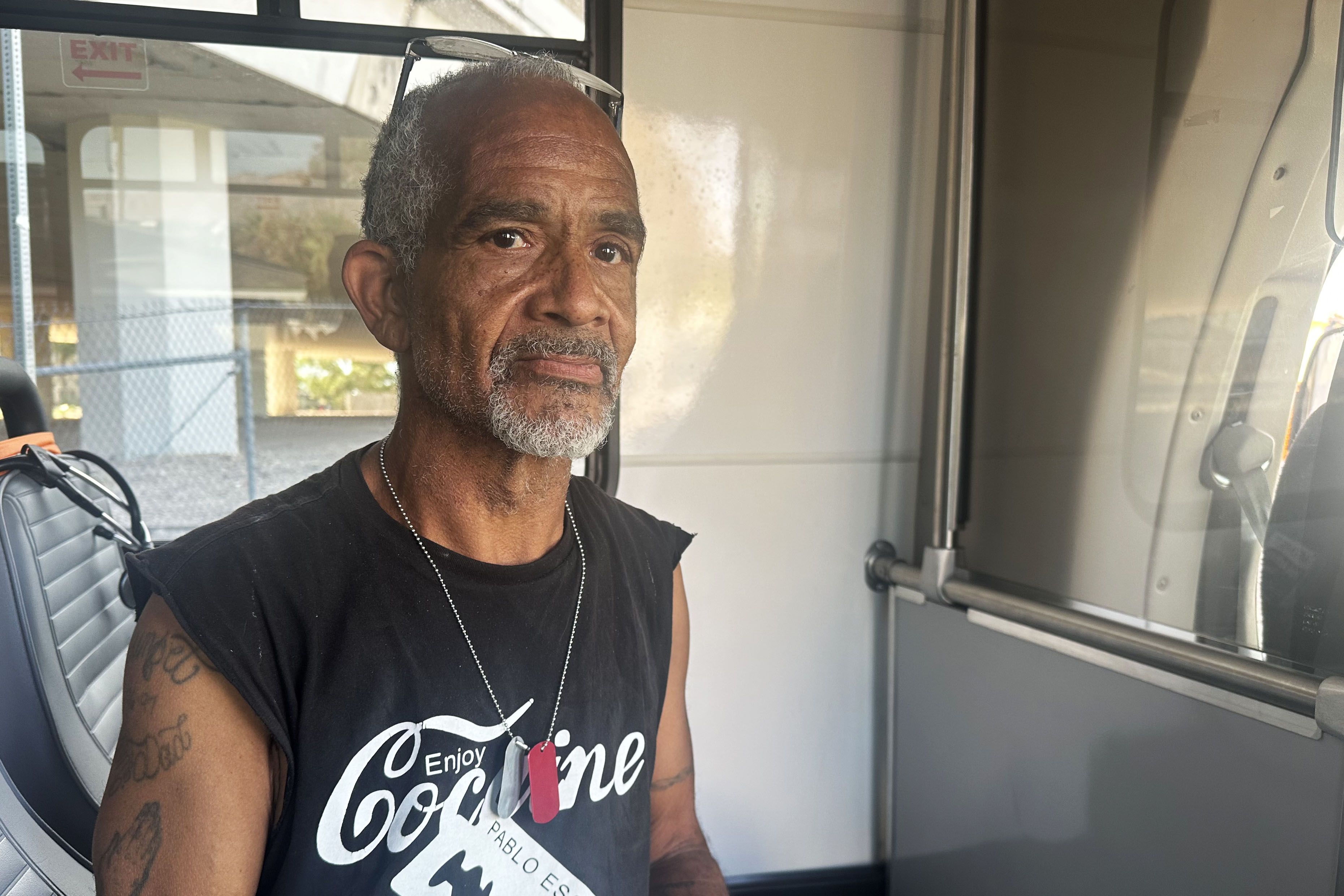

Greedy his toothbrush after cleansing up in his tent on a latest morning, Clark, 45, recalled taking his housing questionnaire this 12 months. He ticked off responses to outreach employees that ought to rank him excessive within the queue — he lacked steady housing, has been homeless for practically 4 years, and has no job or dependable revenue.

He’d frequented emergency rooms and had been to jail, pleading responsible to a felony theft crime he mentioned he didn’t commit, and several other instances for possession of medicine and paraphernalia, he instructed them. He used methamphetamine, principally to be alert at night time when it grew to become harmful. Was he ever assaulted? Sure, particularly in maturity since turning into homeless in 2020.

In actuality, he hustled generally for a dime, and he apprehensive he’d be focused for taking recyclables or partaking in prostitution. “I’ve done it to get a room for a night. It’s like a last resort,” he mentioned.

And Clark wasn’t forthcoming with outreach employees concerning the particulars of his drug use or involvement with regulation enforcement, that he’d bought his physique for intercourse, that he’d skilled abuse. He couldn’t recall all the main points of his medical historical past both. Regularly fleeing regulation enforcement sweeps along with his tent, hauling it alongside busy prepare tracks, he’s excessive at instances, and infrequently in a state of chaos and worry that may scramble his reminiscence or make him scared of arrest. He didn’t share with them his occasional ideas of suicide or his well being issues, together with probably having diabetes.

“They asked me about drugs, I was like, um, I don’t know,” Clark mentioned. “Like I’m supposed to tell them I got addicted to meth or sold my body for a meal and hotel room? I had no idea where this information was going or what it was being used for.” After he took the survey, no housing got here.

Even those that do reply actually discover themselves competing for a restricted provide of inexpensive housing. John Harris was sleeping underneath a bridge on a latest October afternoon. He mentioned he has taken the questionnaire twice. It led nowhere.

“They asked me, have I been incarcerated? And I said yes. I’ve been to prison too many times. And I have mental health struggles,” mentioned Harris, 59, who has been out and in of sober dwelling shelters however nonetheless makes use of methamphetamine. He has been a repeat customer to emergency rooms, and on an October afternoon recorded a hypertension studying that put him in danger for a coronary heart assault — components that ought to rating factors for vulnerability.

“I called and asked what happened with my housing. They said I didn’t score high enough,” he mentioned. After getting his blood stress checked by a road drugs nurse, he shrugged, saying he may wind up again within the emergency room, as he retreated underneath the bridge.

“No matter what society says today, things ain’t never going to change,” he mentioned.

‘I Don’t Know What the Resolution Is’

How communities assign factors to homeless individuals and rank them for housing is the largest downside.

The most typical questionnaire deployed by communities across the nation, the VI-SPDAT, assigns factors meant to gauge the vulnerability of an individual dwelling on the streets. Specialists say this mannequin was by no means examined as a housing evaluation device, nor meant to find out whether or not somebody will get into housing.

“This is not a reliable instrument, and Black men consistently score the lowest for vulnerability, so they are deprioritized for housing — to get housing, you really need to score high,” mentioned Courtney Cronley, a College of Tennessee researcher who analyzed the vulnerability evaluation. Her findings have been printed in 2020 within the Journal of Social Misery and Homelessness.

Cronley pointed to a spread of questions that exacerbate racial bias and have little to do with qualifying for housing:

What number of instances have you ever acquired well being care in an emergency room? Have you ever been attacked or overwhelmed up? Have you ever threatened to hurt your self or anybody else within the final 12 months?

Does anybody power you or trick you to do issues that you do not need to do? Do you trade intercourse for cash? Run medicine?

Specialists who research the vulnerability questionnaire additionally level out that the racial or ethnic background of surveyors typically doesn’t mirror that of the individuals being questioned, which may result in inaccurate outcomes if a respondent doesn’t really feel secure or perceive the survey’s function.

Some cities and counties are creating surveys that native homeless companies hope will slender racial disparities.

Clark County deployed a brand new vulnerability evaluation in June after a 2023 secret-shopper challenge discovered the system was not connecting homeless individuals with housing or companies, particularly individuals of colour.

“We failed in every category,” Barnes mentioned. Previously homeless individuals fanned out on the streets and within the tunnels to check whether or not the housing questionnaire resulted in offering housing for probably the most weak. “All we were doing is counting people.”

Clark County’s new weighted questionnaire now considers how possible an individual is to exit homelessness on their very own — as an alternative of how possible they’re to die on the streets or within the tunnels.

The brand new system assigns homeless individuals factors in 4 classes to get greater within the queue for housing: whether or not somebody is pregnant or a father or mother; whether or not they have a substance use dysfunction, continual well being situation, or psychological well being prognosis; whether or not they’re 55 or older; and whether or not they have dedicated a felony or violent crime.

“Because you’re not going to get approved for a job or housing if they run a background check and there’s a criminal record,” she mentioned, “so we want to address that in our housing system.”

Nonetheless, Barnes isn’t certain Clark County will get it proper this time. As of mid-November, extra homeless Black individuals have been ready for housing than white individuals. In accordance with native information obtained by public information requests, practically 1,500 Black persons are within the county’s housing queue, in contrast with roughly 1,000 white individuals.

“I don’t know what the solution is,” Barnes mentioned. “To be honest, the numbers may spike again.”

Los Angeles County, the place an estimated 75,000 individuals expertise homelessness, is making a weighted device to assign extra factors for components that disproportionately have an effect on individuals of colour.

If somebody has been incarcerated or detained by regulation enforcement, as an alternative of getting one level, a homeless particular person would rating 5, transferring them up on the housing record, mentioned Eric Rice, a social scientist and professor on the College of Southern California.

“We are assigning more points to structural inequities,” mentioned Rice, who helps develop the brand new questionnaire.

Los Angeles County additionally plans to assign extra factors for drug use and for having HIV, which impacts Black males greater than another group. New HIV diagnoses for Black adults have been eight instances these of white individuals, in line with analysis by KFF, a well being data nonprofit that features KFF Well being Information.

Homelessness coordinators have additionally revamped their vulnerability evaluation in Travis County, Texas, the place a Black resident is six instances as prone to fall into homelessness as a white particular person.

The county’s homelessness company, in line with Fisher, checked out traditionally Black neighborhoods in Austin that had been gentrified and scored homeless individuals greater in the event that they’d lived in these areas however have been now homeless.

“If you lived in a place that was previously redlined or now gentrified, you got a point for that,” Fisher mentioned. The survey additionally gave factors for involvement within the felony justice system, as a result of Black persons are extra prone to get arrested or jailed, she mentioned.

Some specialists say the concept of utilizing a device to rank individuals ought to disappear altogether.

As an alternative, communities ought to have flexibility to tailor their housing sources primarily based on the native wants and demographic make-up of their homeless populations, mentioned Mary Frances Kenion, vice chairman of coaching and technical help on the Nationwide Alliance to Finish Homelessness.

She mentioned communities can domesticate belief between homeless individuals and outreach employees by a one-on-one strategy that may be extra conscious of particular person wants and native housing circumstances, which may higher decide whether or not somebody needs to be moved to the highest of the housing record.

Kenion additionally inspired federal, state, and native governments to reimagine their strategy to prioritizing individuals for housing primarily based not on vulnerability however financial components like revenue, historical past of eviction, or having a felony report. She argued communities ought to commit extra sources to stem the circulate of Black individuals into homelessness.

“If we don’t manage to stop that,” she mentioned, “this is just going to keep getting exponentially worse.”

This text was produced by KFF Well being Information, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially impartial service of the California Well being Care Basis.