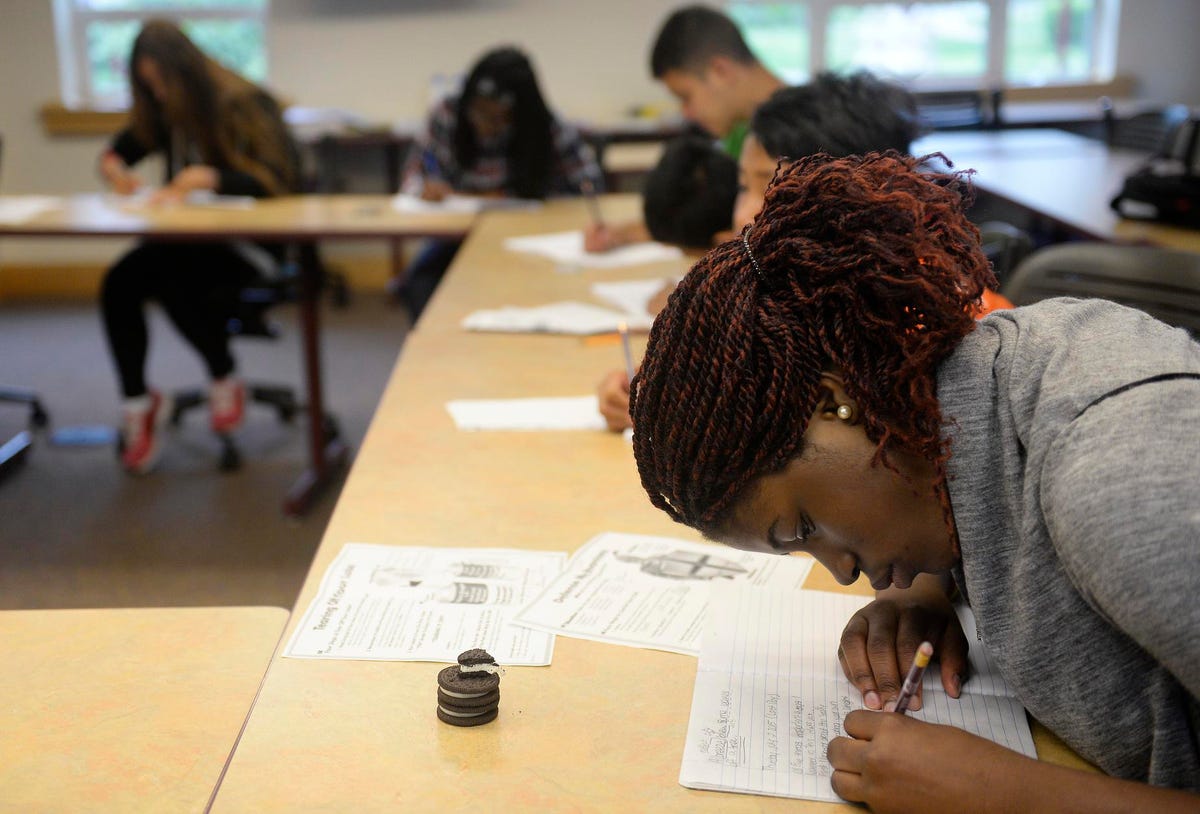

A class in ethnic studies can make a huge difference to students’ experience of education, according … [+]

Some classes are memorable, a few have a lasting impact and a handful change your way of thinking – but one class has a truly remarkable impact that can transform students’ lives for the better.

Students who take a ninth grade ethnic studies class are more likely to engage with school, complete more courses than their peers, graduate from high school earlier and are more likely to enrol in college.

Researchers ascribed the astonishing impact to the ability of the class to enable students to see their community reflected in the curriculum, making school feel relevant and contributing towards a sense of belonging.

Learning about stereotypes and oppression also reminds students that not every failure is the fault of the individual, researchers argued.

The findings come at a crucial juncture for the place of ethnic studies in the school curriculum.

The role of critical race theory (CRT) – that social and institutional dynamics, rather than individual prejudices alone, are responsible for disparate racial outcomes – has become a touchstone issue for both right and left.

MORE FOR YOU

While CRT has taken on new prominence as part of the Black Lives Matter campaign, there have also been calls to ban both it and The 1619 Project – an attempt to put the consequences of slavery at the heart of America’s national narrative – from the school curriculum.

But the impact of the ethnic studies class suggests that engaging with issues of race and ethnicity in the classroom can be a powerful tool in helping students succeed in schools.

San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) launched a pilot program in 2010 where students were automatically assigned to an ethnic studies course if they had a grade point average of 2.0 or less. Around nine in 10 of these students were Hispanic, Black or Asian.

The course aims to provide “culturally relevant” content, looking at the role of different ethnic groups in history, including the experiences of marginalized groups and the impact of discrimination.

Although the principles of the course remain constant, teachers can tailor the content according to the ethnic and racial composition of the class.

An early study found that students on the course had higher attendance, grade point averages and credits, but, as with many other promising interventions, there was a risk the gains could be largely temporary.

But, if anything, the benefits seem to have grown. Students who took the class attended school for an extra one day every two weeks on average throughout the rest of their time in high school, according to a new study by researchers at Stanford, Massachusetts and California universities.

By their fourth year of high school they had passed six more courses than a comparison group. More than nine in 10 graduated within five years, compared with three quarters of their peers. They were 15% more likely to enrol in college within six years.

There are strong reasons to believe that courses such as this can change a student’s learning trajectory, according to Thomas S. Dee, professor at Stanford Graduate School of Education and co-author of the study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The ethnic studies course shares features with targeted interventions that promote a sense of belonging, bolster personal values and address stereotypes, that have all shown the potential to boost engagement, he said.

And the study shows “compelling and causally credible evidence on the power of this course to change students’ life trajectories,” he added.

“There’s long-standing evidence that many historically underserved students experience school environments as unwelcoming, or even hostile,” said Dee.

Ethnic studies gave students “the opportunity to see their community reflected in the curriculum,” said Sade Bonilla, assistant professor at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and co-author of the study.

Learning about their ancestors’ contributions helped develop a sense of pride and contributed towards a sense of belonging, as well as making school feel relevant, she added.

The success of the course prompted SFUSD’s board to vote this spring to make the ethnic studies class a high school graduation requirement.

“The biggest thing that happens in an ethnic studies course, is that students get to approach an academic course from the perspective of their own experience,” said Bill Sanderson, assistant superintendent of high schools at SFUSD.

“Everything is approached in the course from the experience of the students.”

But while the success of the class is astounding, Dee sounds a note of caution. Replicating its impact requires training and careful implementation, he said.

SFUSD developed its course over several years with faculty from San Francisco State’s ethnic studies program, where many of the teachers involved had learned to manage debate on sensitive topics.

“Consider the potential educational and political fallout of asking teachers to discuss unusually sensitive topics in the classroom without the proper training to do so effectively,” Dee added.

Nevertheless, the remarkable impact of a single class is testament to what could be done if schools are able to adopt a more sensitive approach to issues around race and ethnicity.