SIKESTON, Mo. — I wasn’t certain if visiting a cotton subject was a good suggestion. Nearly everybody in my household was antsy once we pulled as much as the ocean of white.

The cotton was stunning however soggy. An autumn rain had drenched the dust earlier than we arrived, our sneakers sinking into the bottom with every step. I felt like a stranger to the soil.

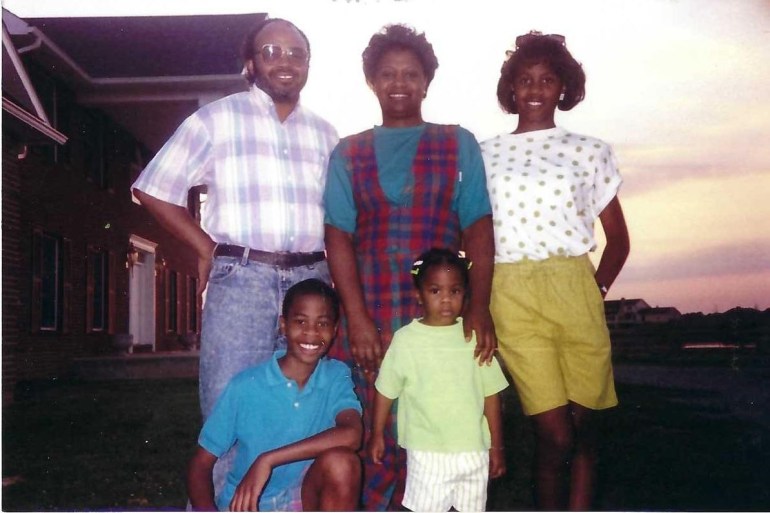

My daughter, Lily, then 5, fortunately touched a cotton boil for the primary time. She mentioned it regarded like mashed potatoes. My dad posed for a couple of pictures whereas I attempted to take all of it in. We have been standing there — three generations sturdy — on the sting of a cotton subject 150 miles away from residence and many years faraway from our personal previous. I hoped this was a chance for us to know our story.

As a journalist, I cowl the methods racism — together with the violence that may include it — can affect our well being. For the previous few years, I’ve been engaged on a documentary movie and podcast referred to as “Silence in Sikeston.” The mission is about two killings that occurred many years aside on this Missouri metropolis: a lynching in 1942 of a younger Black man named Cleo Wright and a 2020 police taking pictures of one other younger Black man, Denzel Taylor. My reporting explored the trauma that festered within the silence round their killings.

Whereas I interviewed Black households to be taught extra concerning the impact of those violent acts on this rural neighborhood of 16,000, I couldn’t cease enthusiastic about my circle of relatives. But I didn’t know simply how a lot of our story, and the silence surrounding it, echoed Sikeston’s trauma. My father revealed our household’s secret solely after I delved into this reporting.

My daughter was too younger to know our household’s previous. I used to be nonetheless making an attempt to know it, too. As a substitute of making an attempt to elucidate it immediately, I took everybody to a cotton subject.

Cotton is sophisticated. White folks received wealthy off cotton whereas my ancestors acquired nothing for his or her enslaved labor. My grandparents then labored onerous in these fields for little cash so we wouldn’t should do the identical. However my dad nonetheless smiled when he posed for an image that day within the subject.

“I see a lot of memories,” he mentioned.

I’m the primary technology to by no means dwell on a farm. Many Black Individuals share that have, having fled the South throughout the Nice Migration of the final century. Our household left rural Tennessee for cities within the Midwest, however we hardly ever talked about it. Most of my cousins had seen cotton fields solely in motion pictures, by no means in actual life. Our dad and mom labored onerous to maintain issues that approach.

On the subject that day, my mother by no means left the van. She didn’t have to see the cotton up shut. She was round Lily’s age when her grandfather taught her easy methods to decide cotton. He had a third-grade schooling and owned greater than 100 acres in western Tennessee. Typically she needed to keep residence from faculty to assist work that land whereas her friends have been in school. She would watch the varsity bus move by the sphere.

“I would just hide, lying underneath the cotton stalks, laying as close to the ground as I could, trying to make sure that no one would see me,” my mother mentioned. “It was very embarrassing.”

She didn’t discuss to me about that a part of her life till we traveled to Sikeston. Our journey to the cotton subject opened the door to a dialog that wasn’t simple however was crucial. My reporting sparked comparable onerous conversations with my dad.

As a toddler, I overheard adults in my household as they mentioned racism and the artwork of holding their tongues when a white individual mistreated them. On my mom’s facet of the household, once we’d collect for the vacations, aunts and uncles mentioned cross-burnings within the South and within the Midwest. Even within the Nineties, somebody positioned a burning cross outdoors a college in Dubuque, Iowa, the place certainly one of my family members served as town’s first Black principal.

On my father’s facet of the household, I heard tales a couple of relative who died younger, my great-uncle Leemon Anthony. For many of my dad’s life, folks had mentioned my great-uncle died in a wagon-and-mule accident.

“There was a hint there was something to do with it about the police,” my dad informed me not too long ago. “But it wasn’t much.”

So, years in the past, my dad determined to analyze.

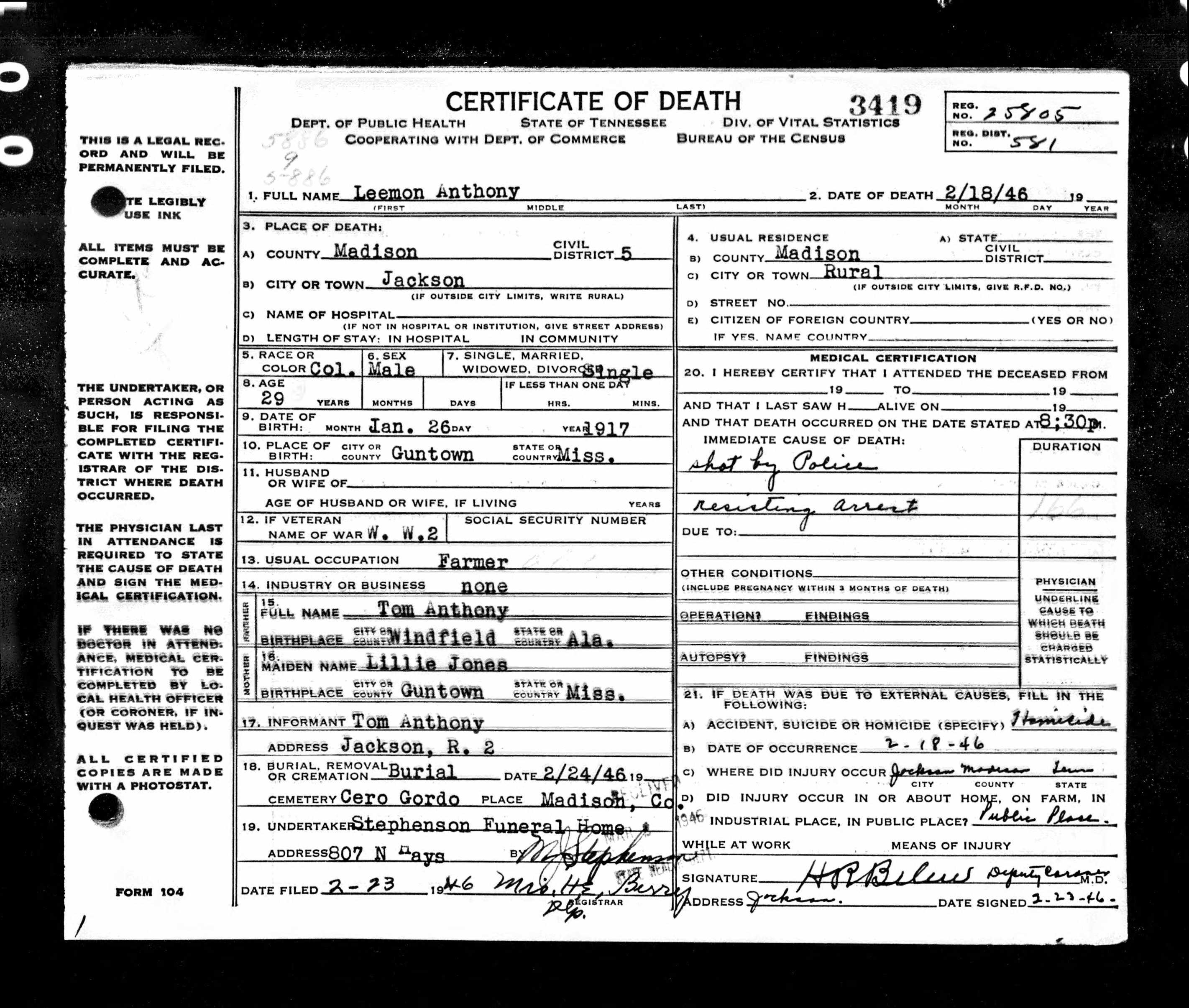

He referred to as up members of the family, dug by way of on-line newspaper archives, and searched ancestry web sites. Finally, he discovered Leemon’s loss of life certificates. However for greater than a decade, he stored what he discovered to himself — till I began telling him concerning the tales from Sikeston.

“It says ‘shot by police,’ ‘resisting arrest,’” my dad defined to me in his residence workplace as we regarded on the loss of life certificates. “I never heard this in my whole life. I thought he died in an accident.”

Leemon’s loss of life in 1946 was listed as a murder and the officers concerned weren’t charged with any crime. Each element mirrored modern-day police shootings and lynchings from the previous.

This younger Black man — whom my household remembered as fun-loving, outgoing, and good-looking — was killed with none court docket trial, as Taylor was when police shot him and Wright was when a mob lynched him in Sikeston. Even when the lads have been responsible of the crimes that prompted the confrontations, these allegations wouldn’t have triggered the loss of life penalty.

At a listening to in 1946, a police officer mentioned that he shot my uncle in self-defense after Leemon took the officer’s gun away from him thrice throughout a combat, in response to a Jackson Solar newspaper article my dad discovered. Within the article, my great-grandfather mentioned that Leemon had been “restless,” “absent minded,” and “all out of shape” since he returned residence from serving abroad within the Military throughout World Battle II.

Earlier than I might ask any questions, my dad’s cellphone rang. Whereas he regarded to see who was calling, I attempted to assemble my ideas. I used to be overwhelmed by the main points.

My dad later gently jogged my memory that Leemon’s story wasn’t distinctive. “A lot of us have had these incidents in our families,” he mentioned.

Our dialog happened when activists all over the world have been talking out about racial violence, shouting names, and protesting for change. However nobody had accomplished that for my uncle. A painful piece of my household’s story had been filed away, silenced. My dad gave the impression to be the one one holding area for my great-uncle Leemon — a reputation that was not spoken. But my dad was doing it alone.

It looks as if one thing we must always have mentioned as a household. I puzzled the way it formed his view of the world and whether or not he noticed himself in Leemon. I felt a way of grief that was onerous to course of.

So, as a part of my reporting on Sikeston, I spoke to Aiesha Lee, a licensed counselor and Penn State College assistant professor who research intergenerational trauma.

“This pain has compounded over generations,” Lee mentioned. “We’re going to have to deconstruct it or heal it over generations.”

Lee mentioned that when Black households like mine and people in Sikeston discuss our wounds, it represents step one towards therapeutic. Not doing so, she mentioned, can result in psychological and bodily well being issues.

In my household, breaking our silence feels scary. As a society, we’re nonetheless studying easy methods to discuss concerning the nervousness, stress, disgrace, and concern that come from the heavy burden of systemic racism. All of us have a duty to confront it — not simply Black households. I want we didn’t should take care of racism, however, within the meantime, my household has determined to not undergo in silence.

On that very same journey to the cotton subject, I launched my dad to the households I’d interviewed in Sikeston. They talked to him about Cleo and Denzel. He talked to them about Leemon, too.

I wasn’t enthusiastic about my great-uncle after I first packed my baggage for rural Missouri to inform the tales about different Black households. However my dad was holding on to Leemon’s story. By maintaining the file — and eventually sharing it with me — he was ensuring his uncle was remembered. Now I say every of their names: Cleo Wright. Denzel Taylor. Leemon Anthony.

The “Silence in Sikeston” podcast from KFF Well being Information and GBH’s WORLD is obtainable on all main streaming platforms. A documentary movie from KFF Well being Information, Retro Report, and GBH’s WORLD will air at 8 p.m. ET on Sept. 16 on WORLD’s YouTube channel, WORLDchannel.org, and the PBS app. Preview the trailer for the movie and the podcast. Extra particulars about “Silence in Sikeston.”