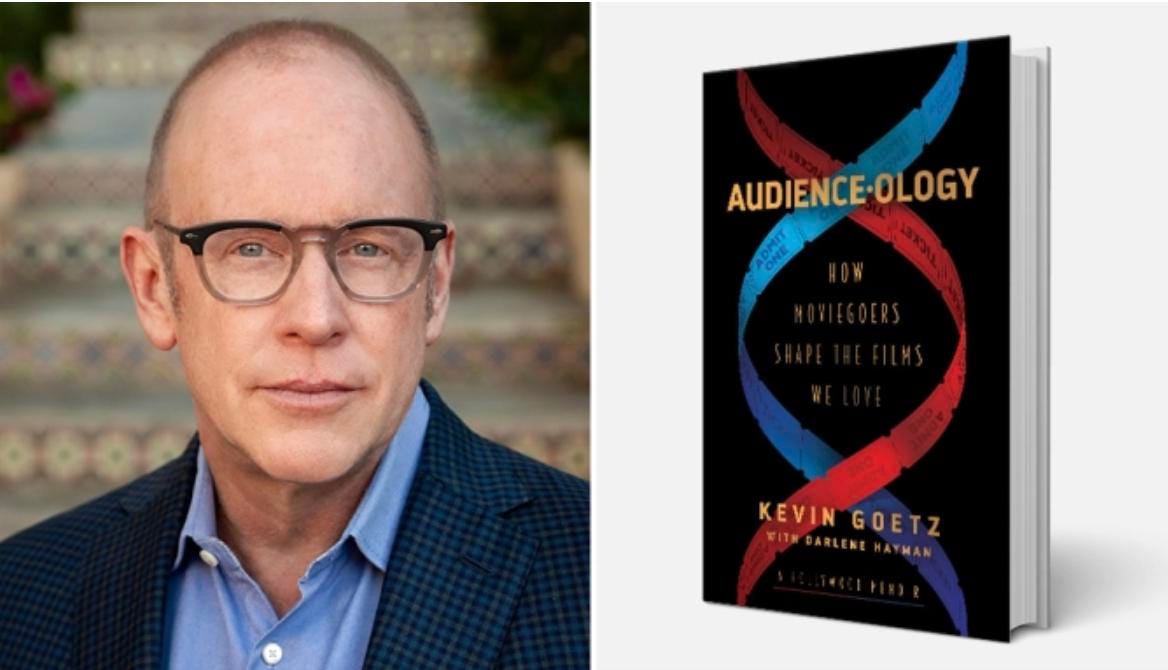

(Images courtesy of Kevin Goetz, Tiller Press)

The movies you see on screens big and little these days typically don’t start out the way they end up, thanks to a coterie of little-known market-research companies who help executives and creators fine-tune movies, TV shows, streaming projects and even video games before they go out in the world, based on what test audiences’ reactions.

Now, the founder and CEO of one of those companies, Kevin Goetz of Screen Engine/ASI, has co-written Audience-ology, a book of war stories and lessons learned in working with movie studios, directors, producers and executives to turn rough cuts into market winners.

By his count, Goetz has seen more than 7,000 movies in a combined 20,000 test screenings over 35 years in and around the business (he’s also a former actor and continues to produce films).

By now, Goetz has a sense of what works and doesn’t, like his near-algorithmic readout of audience applause (or lack of it) at the end of those test screenings. The longer and more enthusiastic that group response, the better. It suggests, though not always definitively, how well the movie will be received by broader audiences.

But for all his own gut instincts, Goetz depends mostly on what he gleans detailed post-screening discussions with focus groups made of some of those audience members. In such assessments, data wins. Indeed, Goetz points out his own gut’s fallibility by opening the book with a story about his skepticism regarding commercial prospects for Robert Zemeckis’ Forrest Gump.

That 1994 movie, of course, went on to gross more than $678 million (back when that was real money), win the Best Picture Oscar and five others, and become a cultural touchstone of that decade. Goetz lost a $1 bet, but also earned a bit of humility about the power of gut instincts. Now, he relies on the data.

MORE FOR YOU

As he points out, test screenings date back a century, to Harold Lloyd, Buster Keaton, and Charlie Chaplin in the film industry’s earliest days. Even then, those pioneers would take bits of his silent films and test them with audiences at Hollywood Boulevard theaters in Los Angeles before releasing the full films.

“We often see filmmaking as something separate and apart from this trend of data-driven decision-making,” Goetz writes. “We like to think of directors as auteurs and their films as wonderful, original pieces of art that have sprung, fully formed, from their minds. Some are something close to that. But most films can benefit from an intensive process of viewer testing, analysis, and analytics-driven editing. And that includes movies that have captured awards from the world’s most prestigious avant-garde film festivals.”

The business has evolved remarkably since Chaplin, Keaton and Lloyd, but the terror of the test screening has not. Goetz quotes Oscar and Emmy winner Ed Zwick (Shakespeare in Love, Thirtysomething), who says, “It’s like seeing your lover naked for the first time” when the first test audiences see a project that may have been many years in the making.

“A test screening is judgment time, the moment of reckoning, the moment of truth,” Goetz writes. “For the audience, it’s a few hours of their day. But for the people involved in making the movie, it’s often the climax of many years of their lives. It can also be their career-defining moment, and the results determine how the next chapter of their career will play out.”

Test screenings are expanding well beyond the movie business, especially as more feature-length projects head to streaming services first or nearly simultaneously with any theatrical release.

Ask him how much the test process has changed, and Goetz says, “Not that far, meaning, there’s always going to be people who love content. There’s always going to be content. That is for sure. And we know that with the proliferation of the streaming services, and what’s occurred in terms of series and movies, that it’s just endless. In fact, I would argue that it’s only gotten far more intense.”

But there have been changes, in part because of streaming, and in part because of what the pandemic has done to theater-going, and testing for shows that may run somewhere other than on a giant screen in a building far from home.

As Goetz wrote, “The industry is evolving, and movie consumers aren’t necessarily moviegoers.”

One big difference is the agency of audiences these days. They can access thousands of features and series on any of the major streaming services, and can click away in a second if the show isn’t interesting.

“We always had the distributor in charge of the messaging, right?” Goetz said. “Here are the movies coming out, choose from two of them, three of them. That’s it. And if you don’t like it, lump it.”

Audience patience for self-indulgent or unfocused projects is definitely waning. For one thing, directors and studios are being forced to trim the length of projects, and make sure the endings make sense.

“When the pandemic started, it was really tough, because I saw so many movies that were too long, and their endings were really weird,” Goetz said. “It was just a free-for-all, because people were so anxious to get their content (distributed) because they were so nervous about the pandemic. So they didn’t really do a lot of testing in that (first) year period. There were not a lot of great movies that I saw during that time. There were a lot of, I think, indulgent movies, and movies that had endings that didn’t pay off or were strong enough.”

Streaming services are now embracing test screenings, especially after Screen Engine launched VirtuWorks, an online testing system that allows executives to monitor and replay the reactions of dozens of viewers simultaneously. The shift turned out to be “a happy discovery for many clients, particularly for the streaming services, and the perfect way in which to test content for in-home viewing.”

Even before the pandemic, Screen Engine would screen shows headed to streaming in smaller theaters, with recliner seats and easy access to food, to better mimic how the audience would watch at home. VirtuWorks takes it to the next level in terms of reflecting the way online audiences will ultimately watch a show.

Now, even theater-bound movies are getting early-round tests online, because “you just need a smaller number of folks just to be exposed to the film, to have a laboratory to play with. I actually see movies getting better as a result of this.”

Asked where he sees the industry going, Goetz says, “To me, the biggest change is people want to see lots of different things but they want to see more carnival rides or eventized entertainment in the theater. People are making more difficult choices now because of the (wide selection), the price, and convenience converging together for the first time in this perfect storm. Someone described a movie I tested the other night as a female Shawshank Redemption. And everyone was saying afterwards, ‘Well, I’ll take that.’ And I’m thinking to myself, ‘Well, no one would make Shawshank Redemption theatrically today.’ It would never be (a) theatrical (release), because who would take the risk?”

The industry is learning, at great expense, that many pricey would-be blockbusters greenlit and produced before the pandemic, and only released this year, don’t translate for the audiences that now actually go to theaters.

Spider-Man: No Way Home can gross more than $1 billion worldwide (a pandemic-era record), while Guillermo del Toro’s Nightmare Alley, Steven Spielberg’s West Side Story remake, and even the new James Bond film, No Time To Die can’t entice core parts of their audience to venture into theaters.

That’s fueled another growth area for Goetz and Screen Engine/ASI: “capability testing,” figuring out on the front end, before a frame is shot, whether a project can carry the financial expectations of a theatrical release. For an increasing number of projects, they’ll need to go straight to streaming, likely with a smaller production budget, and definitely with a different kind of marketing approach.

“So you have to then make the decision before and not after: ‘Is this a movie that’s going to a streamer, or it’s going to streaming because you can’t make it for too much money?’ That cannot be overstated: It’s much better to predetermine what the movie’s fate is, from a budgetary standpoint, before you begin shooting a frame of film.”

That may kill some projects, or force a substantial restructuring before they get a green light. What gets lost? Goetz circles back to Forrest Gump, a distinctive project with an inexplicable title.

Forrest Gump almost certainly wouldn’t get made for theatrical release these days, though it could still find a big audience online, somewhat like Fast Times at Ridgemont High had a huge second life in home video after its studio miscalculated interest in the initial theatrical release of Amy Heckerling’s classic teen tale.

The vast array of options, both in things to watch and places to watch them, mean that content and distribution are no longer quite the kings they once were of the business. Goetz suggests highly targeted marketing that can make a project standout for a well-defined audience will be the key to success for many films and other projects in the future. And that too has become a growth opportunity for Screen Engine/ASI.

“Getting people to pay attention to all this fabulous, incredible content is really tough,” Goetz said. “So what’s been more effective is we’ve had to pivot (to) advertising testing, where we test advertising content. Digital advertising has different rules and ways of reaching people than traditional linear trailers and 30-second commercials.”

Despite all the changes, Goetz remains sanguine about the future of entertainment, if not of movie theaters, which face a demographic cliff as their loyal Baby Boomer audiences stop going, and eventually die off. GenZ audiences aren’t interested in seeing much of anything in theaters except big event projects, which will shift even more what gets the green light going forward.

“We hold a certain nostalgia (for theaters), but younger people don’t have that,” Goetz said. “They don’t need to see things (in theaters) unless they’re of a certain kind of elevated fun and spectacle. So there has to be a consolidation, or shrinking of screens. It’s not going anywhere, it’s just here’s the numbers, here’s the facts.”