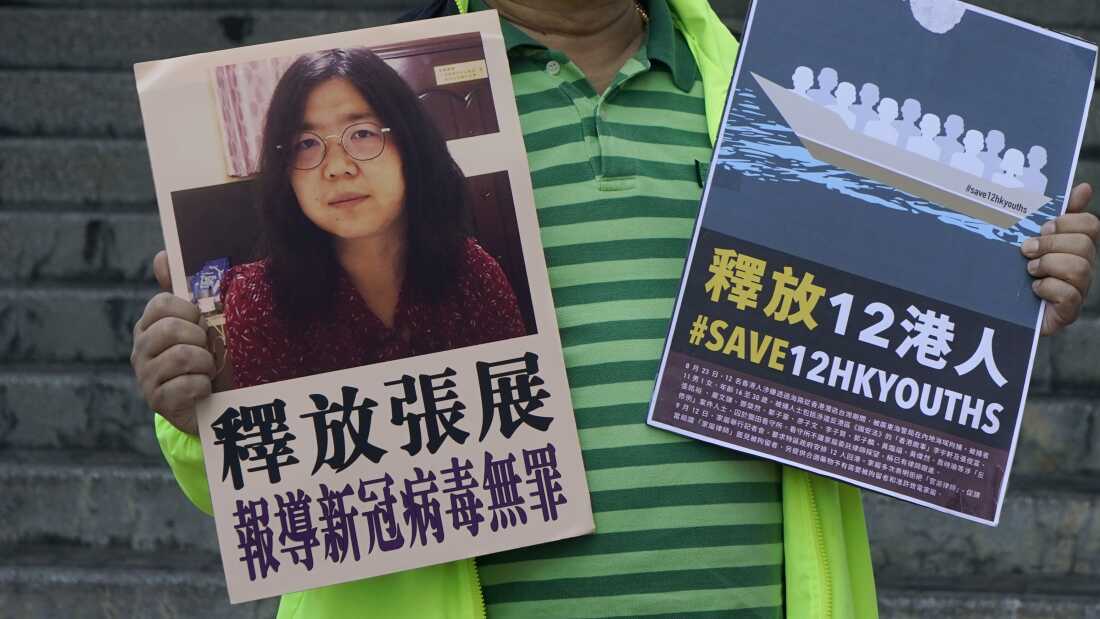

A professional-democracy activist holds placards with the image of Chinese language citizen journalist Zhang Zhan exterior the Chinese language central authorities’s liaison workplace in Hong Kong on Dec. 28, 2020.

Kin Cheung/AP

disguise caption

toggle caption

Kin Cheung/AP

A professional-democracy activist holds placards with the image of Chinese language citizen journalist Zhang Zhan exterior the Chinese language central authorities’s liaison workplace in Hong Kong on Dec. 28, 2020.

Kin Cheung/AP

TAIPEI, Taiwan — When former lawyer Zhang Zhan posted lots of of movies from Wuhan in the course of the chaotic early months of the COVID-19 outbreak, she turned one among China’s most outstanding citizen journalists. Jailed in 2020 for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” — a cost Chinese language authorities usually use towards journalists and activists — she was sentenced just lately to a different 4 years for a similar offense. Aleksandra Bielakowska of rights group Reporters With out Borders (recognized by its French initials, RSF) known as the choice contemporary proof of how far Beijing has gone to silence impartial reporting.

Rights teams say Zhang’s case is a part of a broader regional pattern. Detentions of journalists and media employees throughout the Asia-Pacific area climbed steadily from a complete of 69 in 2010 to 229 in 2020 (the yr of Zhang’s first arrest amid the COVID pandemic), spiking to an all-time excessive of 334 in 2022 earlier than tapering barely to 300 final yr, an evaluation of RSF information exhibits. Main international locations driving that pattern have been China, Afghanistan, Vietnam and Myanmar. It is taking place because the U.S. cancels funding for impartial media throughout the area, and China exports surveillance strategies past its borders.

Press freedom teams rank China because the world’s high jailer of journalists, with 112 journalists and media employees at present behind bars, alongside one other eight in Hong Kong within the wake of Beijing’s imposition of a nationwide safety legislation there in 2020.

Myanmar emerged as one other outstanding jailer following its 2021 coup and civil warfare, with 51 journalists at present in detention.

Ross Tapsell, an affiliate professor at Australian Nationwide College who researches media and tradition in Southeast Asia, says the disaster is not restricted to the headline-grabbing crackdowns. “There is no one cause behind the region’s decline in press freedom,” he says. “It correlates with what we’re seeing with democracy in the region, and indeed globally — you’re seeing a slow decay, like ice melting.”

Philippines: When speaking the speak is not sufficient

Philippines’ President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. gestures to military officers as he delivers a speech in the course of the 128th founding anniversary of the Philippine military at its headquarters in Manila on March 22.

Ted Aljibe/AFP through Getty Photographs

disguise caption

toggle caption

Ted Aljibe/AFP through Getty Photographs

Former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, who now faces expenses of crimes towards humanity within the Hague, got here into workplace in 2016 labeling the media as enemies. Violence towards journalists rose sharply beneath his administration, which continued till 2022. Information from the Philippine Heart for Investigative Journalism exhibits that, within the first 28 months of Duterte’s presidency, there have been 99 recorded assaults and threats on media employees. By Could 2021, that determine reached 223 — with state brokers linked to roughly half of these circumstances. The middle counted a complete of 22 media employees killed from 2016 to 2022.

Tensions escalated in 2020 when Duterte’s administration compelled ABS-CBN, one of many nation’s most outstanding cable information networks, off the air.

President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. took a softer tone when he assumed energy in 2022, however journalists say underlying violence has intensified. Simply midway by means of Marcos’ time period, documented assaults and threats towards journalists have risen by 44% in contrast with Duterte’s total time period, based on the investigative journalism heart.

“What tops the list is intimidation,” says Rhea Padilla, the information director of AlterMidya, a nationwide community of native media shops within the Philippines.

“Journalists are often labeled as communists or terrorists,” Padilla says. “It’s not just name-calling. It really puts lives at risk. It justifies surveillance, it justifies arrest.”

Workers and supporters of ABS-CBN mild candles in entrance of its major studio to point out assist as ABS-CBN Information airs its last program within the provinces on Aug. 28, 2020, in Manila, Philippines.

Jes Aznar/Getty Photographs

disguise caption

toggle caption

Jes Aznar/Getty Photographs

Jonathan de Santos, a deputy editor at ABS-CBN (which has gone totally on-line since its broadcast suspension) and chair of the Nationwide Union of Journalists of the Philippines, says if Marcos wished to show he would deal with the media otherwise from Duterte, he may begin by restoring ABS-CBN’s license. He may additionally reexamine the case of group journalist Frenchie Mae Cumpio, who stays jailed after 5 years on expenses that rights teams say are fabricated. The nation additionally nonetheless lacks a freedom of knowledge act, and libel stays a felony offense.

Nonetheless, de Santos says journalists are combating again.

“We have seen that an attack on one of our colleagues is an attack on everyone,” he says. Journalists have begun submitting defamation or administrative circumstances towards those that “red-tag” them as communist insurgent supporters, with high-profile latest wins.

The Marcos administration has additionally changed management on the presidential job drive on media safety and barred police from red-tagging journalists — although whether or not that ban will probably be enforced stays unclear.

Indonesia: Extra overt strain

A journalist holds posters throughout an illustration for Worldwide Labor Day at Cikapayang Park in Bandung, West Java, Indonesia, on Could 1.

Ryan Suherlan/NurPhoto through Getty Photographs

disguise caption

toggle caption

Ryan Suherlan/NurPhoto through Getty Photographs

In Indonesia, the Alliance of Unbiased Journalists, one among nation’s most outstanding press freedom organizations, has recorded a steadily rising pattern in bodily violence in direction of journalists since 2020 — with 2023, the final full yr of Widodo’s administration, being the highest yr in a decade.

Bagja Hidayat, an editor on the Jakarta-based journal Tempo, says though former President Joko Widodo was nicer to the media in particular person, harassment started intensifying beneath his time period and has worsened significantly beneath the present President Prabowo Subianto, who took energy final yr.

Tempo has lengthy confronted cyberattacks and doxxing, however earlier this yr the intimidation turned grisly: a decapitated pig’s head was delivered to its workplace, addressed to investigative reporter Francisca Christy Rosana. Bagja says that in Muslim-majority Indonesia, a decapitated pig carries the connotation that killing Tempo’s journalists is permissible.

When requested to answer the incident, presidential spokesperson Hasan Nasbi steered the employees “just cook” the top, based on information studies in March.

“The government has so many influencers aligned with their narrative,” Hidayat says. “Any time we publish a critical story, these people spring into action, buzzing us with videos discrediting us.” Authorities ministries have additionally sued the journal for defamation, he says.

Media scholar Tapsell notes that even in international locations with out mass jailing, “a big part of the problem is just the threat” — of jailing, of promoting being pulled, of newsroom closures. Promoting income plunged throughout COVID-19, and as audiences migrated to social media, “government advertising is now a larger chunk of the pie,” he says. That reliance leaves shops susceptible to state strain.

In the course of the latest protests throughout Indonesia, Tapsell says the broadcasting fee issued a directive discouraging media shops from masking the protests reside. Viewers turned to TikTok for reside footage, solely to see the app briefly pause its “Live” function. He factors to a sample of web slowdowns throughout protests and predicts “more pressure on tech platforms … to reduce the capacity for ordinary citizens to film protests.”

Hong Kong and past

A journalist will get pepper-sprayed after a heated change with police throughout a rally in Hong Kong throughout demonstrations in assist of the Uyghur minority in China, on Dec. 22, 2019.

Anthony Wallace/AFP through Getty Photographs

disguise caption

toggle caption

Anthony Wallace/AFP through Getty Photographs

Rights advocates say though Hong Kong’s press surroundings was a shiny spot in China, media freedoms have deteriorated sharply since Beijing imposed a sweeping nationwide safety legislation in 2020. RSF information exhibits eleven journalists detained there this yr. A number of media shops have closed and lots of of journalists have left the territory.

Shirley Leung, a journalist who relocated to Taiwan, based Photon Media, one among many media platforms that studies on Hong Kong from afar. “We try our best to report on Hong Kong in a way that doesn’t endanger our sources,” she says.

Leung says on high of the high-profile arrests, the territory’s remaining journalists face much less seen strain like tax probes, nameless threats and strain on landlords to not lease to reporters. Many journalists who left the territory discovered work with U.S.-funded shops like Radio Free Asia — however Leung says these shops’ collapse has pushed these reporters again right into a tough scenario.

In the meantime, China’s information-control mannequin is spreading. Rights teams have documented harassment, interrogations and even kidnappings of exiled Chinese language journalists, typically with Southeast Asian governments’ cooperation. Current leaks from a Chinese language tech firm present surveillance instruments much like the nation’s “Great Firewall” being exported to Pakistan, Myanmar and different nations.

Aleksandra Bielakowska of RSF says lately, Chinese language chief Xi Jinping’s administration “introduced sweeping restrictions to make sure media outlets will not be allowed to report freely about what’s going on.”

She herself was detained and deported from Hong Kong in April 2024 whereas attempting to look at media govt Jimmy Lai’s trial. The one unredacted element within the paperwork she later obtained from Hong Kong authorities was her house deal with in Taiwan — “another sign of intimidation,” she says.