“It was either die or do this transplant,” Mr. Bennett said before the surgery, according to officials at the University of Maryland Medical Center. “I want to live. I know it’s a shot in the dark, but it’s my last choice.”

Dr. Griffith said he first broached the experimental treatment in mid-December, a “memorable” and “pretty strange” conversation.

“I said, ‘We can’t give you a human heart; you don’t qualify. But maybe we can use one from an animal, a pig,” Dr. Griffith recalled. “It’s never been done before, but we think we can do it.’”

“I wasn’t sure he was understanding me,” Dr. Griffith added. “Then he said, ‘Well, will I oink?’”

Xenotransplantation, the process of grafting or transplanting organs or tissues from animals to humans, has a long history. Efforts to use the blood and skin of animals go back hundreds of years.

In the 1960s, chimpanzee kidneys were transplanted into some human patients, but the longest a recipient lived was nine months. In 1983, a baboon heart was transplanted into an infant known as Baby Fae, but she died 20 days later.

Pigs offer advantages over primates for organ procurements, because they are easier to raise and achieve adult human size in six months. Pig heart valves are routinely transplanted into humans, and some patients with diabetes have received porcine pancreas cells. Pig skin has also been used as a temporary graft for burn patients.

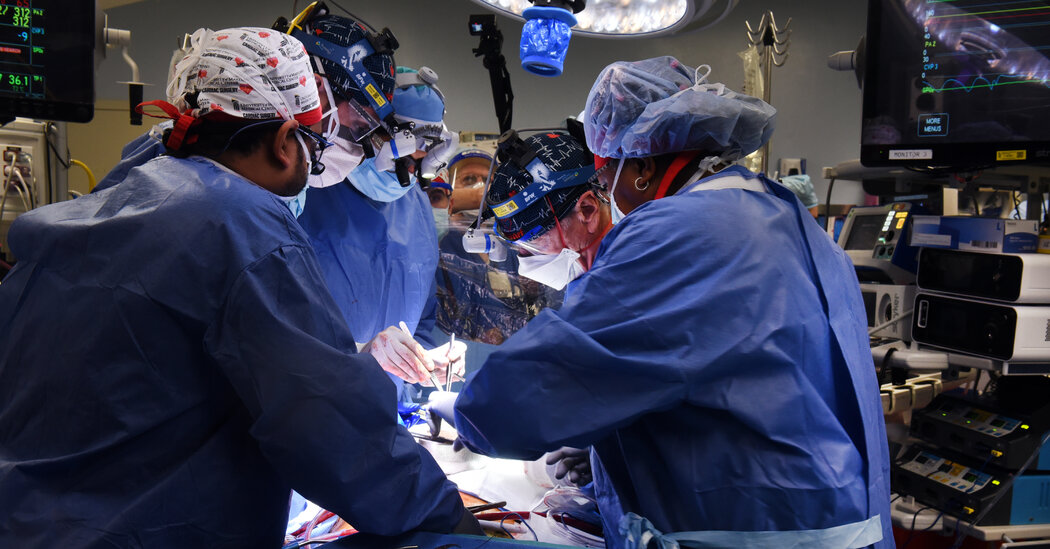

Two newer technologies — gene editing and cloning — have yielded genetically altered pig organs less likely to be rejected by humans. Pig hearts have been transplanted successfully into baboons by Dr. Muhammad Mohiuddin, a professor of surgery at University of Maryland School of Medicine who established the cardiac xenotransplantation program with Dr. Griffith and is its scientific director. But safety concerns and fear of setting off a dangerous immune response that can be life-threatening precluded their use in humans until recently.