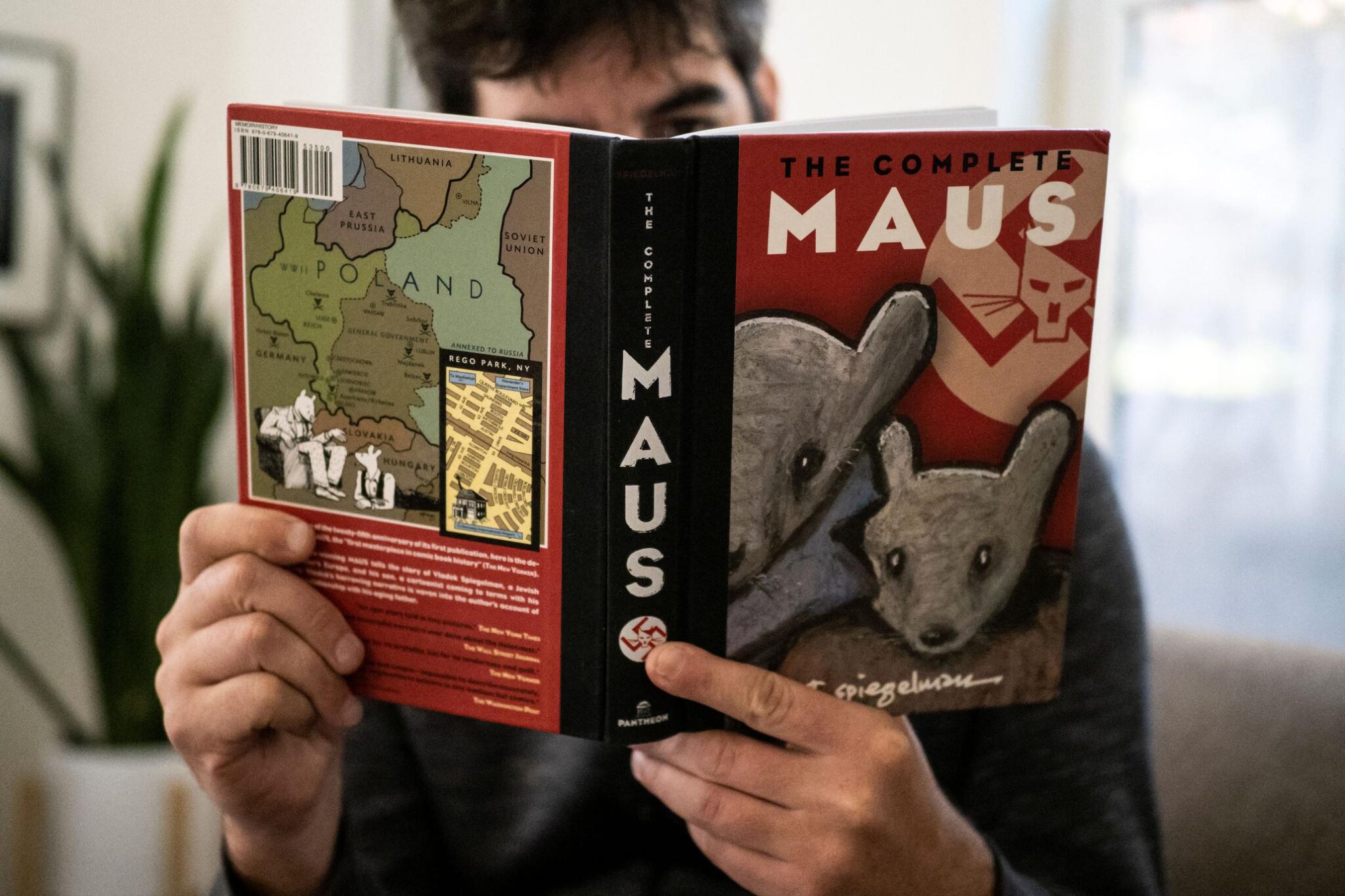

This illustration photo taken in Los Angeles, California on January 27, 2022 shows a person holding … [+]

Earlier this week, a Tennessee school board unanimously voted to remove Maus, a Holocaust-themed graphic novel, from its eighth-grade language arts curriculum, rekindling concerns of censorship of comics and other material aimed at teens and young adults. Maus, by Art Spiegelman, draws on his family’s personal experience surviving a Nazi concentration camp. It was the first graphic novel to win the Pulitzer Prize (in 1992) and is a frequently-cited example to make the case that the comics medium is capable of addressing serious themes in sophisticated ways.

Tennessee officials said they objected to use of several words including “damn,” and the depiction of nudity in one particularly somber moment in the book, though several were quoted as having no particular objections to teaching about the Holocaust per se. But coming amid widespread controversies surrounding the teaching of history in American schools, the board’s decision, which became publicly known the day before Holocaust Remembrance Day, raises more troublesome issues.

The Holocaust Museum posted a defense of the work on Twitter, saying that “Maus has played a vital role in educating about the Holocaust through sharing detailed and personal experiences of victims and survivors. Teaching about the Holocaust using books like Maus can inspire students to think critically about the past and their own roles and responsibilities today.” Of course, preventing that last bit has become a major focus of conservative groups in recent years, from Virginia to Texas and beyond.

I had a chance to speak with Jeff Trexler, executive director of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, about the controversy. The CBLDF has been defending comics creators, publishers and retailers against this kind of censorship since 1986. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Rob Salkowitz, Forbes Contributor: Has the CBLDF been contacted about the situation in Tennessee?

Jeff Trexler, Executive Director, Comic Book Legal Defense Fund: We’re reaching out. Typically, people bring us in when these proposals go through review, but in this case the Board made their decision and announced it as a fait accompli. They didn’t even follow their own process. So we’ve been discussing internally how to best engage.

MORE FOR YOU

RS: What kinds of legal remedies are available for parents and students, or is this more of an issue of applying political pressure?

JT: The legal precedents around book removals are a little bit fuzzy, because the Supreme Court didn’t really decide the central issue. Basically, if it’s a case of removing a book from the library, the protections of the First Amendment apply. But if it’s taking it out of the curriculum, as in this case, the courts often defer to state and local authorities. That’s why we’re seeing so many of these situations around anti-CRT [Critical Race Theory] laws coming up in the context of curriculum, where the law is not settled.

RS: Have these kinds of objections been raised before in the case of Maus?

JT: Maus has been the subject of so many challenges: depiction of different groups, swear words, violence, occasional nudity, even though the nudity in the book is the nakedness of dehumanization, which is the opposite of erotic nudity. What intrigued me about this is their highly legalistic approach to foul language. They argue that the language would be disallowed if a kid used it in school, so we can’t give them books that use this language. But obviously, seeing a word vocalized by characters in specific situations in a book is different than a kid cussing out his teacher.

One of the most troubling objections raised here was someone complaining that Art Spiegelman drew for Playboy and they didn’t want that for the kids. I mean… I guess cancel culture means different things to different people, but that’s classic stigmatization. Based on work he did at one point in his career, his award-winning graphic novel should be ostracized. Is this what we want to be teaching our children? It’s a very cynical, negative and anti-American way to look at books, curriculum, and life.

RS: What do you say to the authorities who claim they have no problem with the thematic content of the work, but object to specific words and images they believe are inappropriate for kids?

JT: What we’ve seen in this challenge is objections to the use of comics arts in the curriculum. One is the assumption that comics are subliterate. They misread something in Maus to assume it was for a third-grade reading level, which it’s clearly not.

But generally, there are calls to take graphic novels out of the curriculum because people fear the power they see in the combination of words and pictures. They see images as particularly dangerous, and when you use the “bad words” in combination with pictures, it’s somehow much more objectionable to them than seeing it in plain print. We’re seeing that in a lot of schools, and specifically here. When they discuss bad language, violence, nudity in Maus, they don’t just say its problematic in itself. They see it as promoting suicidal ideation, violence. They see representation as making it real. It’s a serious misreading of how comics actually work. It’s a pre-21st century way of reading images, and it’s not serving anyone. If kids can’t learn to make sense of visual communication, they will be left out.

RS: Is this move against Maus part of a recent pattern? Generally, what has your organization observed about the trajectory of censorship cases over the past few years?

JT: Yes, it’s definitely a rising tide. We started getting rumblings of things that were coming out in Virginia, and when Youngkin won on the basis of making an issue out of local educational curricula, it was clear we’d be dealing with a wave of this in 22, 24, 26. It’s a viable wedge issue that crosses demographics and ideology, including on the left.

RS: If they come after a book of the stature and historical reputation of Maus, is any work safe?

JT: No. No work is safe. You have to be prepared, because every argument you’re raising against Maus could be raised against works that are canonical in other ways. Lots of “classics” have these same kinds of objections that could be raised. It’s a pincher moment, because both sides recognize comics represent the template for literacy in the 21st century, and just as we need them most, there are people coming for them from across the ideological spectrum.

RS: What can parents and citizens do to prevent this kind of censorship from taking hold in their communities?

JT: It takes tremendous courage. People need to speak out. Not just at school board meetings, but before then. They need to recommend things, communicate how much they value this material and why. Officials assume that if they get one complaint, there are millions more and so they take action. We need to demonstrate the true diversity of the community. There needs to be engagement from the get-go. Right now, we who defend the material are made to be ashamed. They want to stigmatize it, make people afraid to put this on the shelves or in the curriculum. I think it should be the oether way around. We need to get people to feel ashamed to raise these objections, because it’s not who we are. That’s not what this country stands for. Get involved, engaged, help people understand. That’s something we can do before controversy starts.