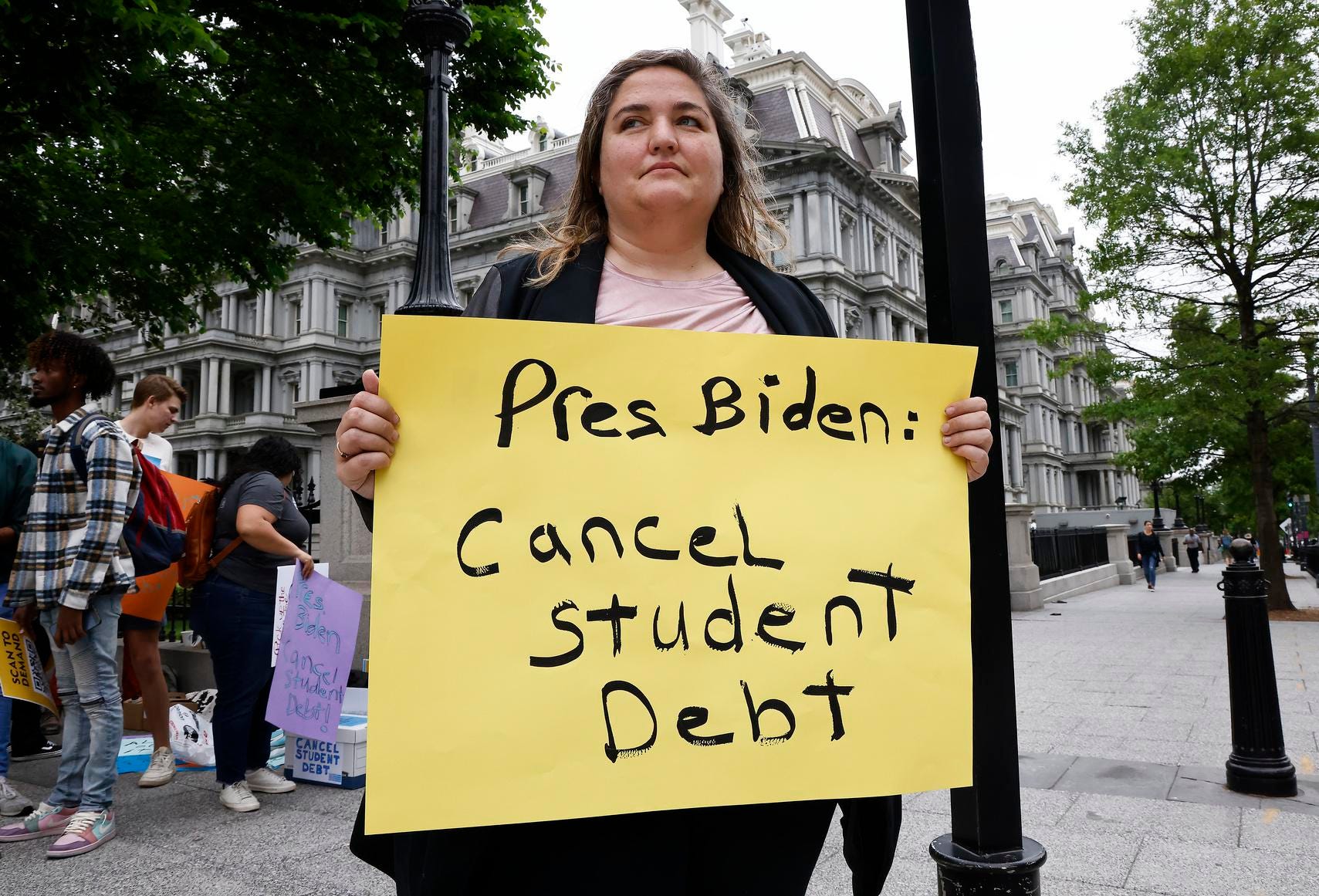

WASHINGTON, DC – MAY 12: Student loan borrowers gather near The White House to tell President Biden … [+]

President Biden’s student loan cancellation program and expansion of income-based repayment plans shredded any pretensions that federal student loans are a fiscally sustainable program. Loans were already losing 10 cents on the dollar, on average, before the president’s actions added $1 trillion to their cost. Going forward, many students will repay half of what they borrowed or less. All this will encourage schools to raise prices to capture the new subsidies.

The irony of loan forgiveness is its backers’ implicit admission about higher education: it’s not always worth it. If college delivered a reliable financial return, there would be no need for these new subsidies; borrowers would be able to pay back their loans with interest. But in reality, many students don’t graduate, while others find their degrees hold little value in the labor market. When accounting for tuition costs, time spent out of the labor force, and the risk of noncompletion, 28% of bachelor’s degrees do not justify the expense.

For the sake of both students and taxpayers, Congress urgently needs to fix federal lending going forward. It should ensure that loans only go to programs with a record of graduating their students and supplying them with the skills they need to land good jobs and repay their debts. Otherwise, in a few years we will be right back where we started: with more student loans going unpaid and more calls for forgiveness.

Hold colleges accountable for unpaid student loans

An effective accountability system will have multiple components. First, the federal government should require colleges to share in the risk of student loan nonpayment. The economic value of higher education is closely related to the rate at which students repay their loans, for the simple reason that student loans are more manageable when tuition is lower and earnings after graduation are higher. Student loan risk-sharing creates an incentive for schools to keep prices down and earnings up.

MORE FOR YOU

Specifically, when students are not on track to fully repay their loans, colleges should pay a penalty equal to a percentage of the unpaid loan balance. Penalty assessments should be progressively higher when loan outcomes are worse.

If borrowers are making progress on their loans but not enough to fully repay them, the college should pay a small penalty, enough to incentivize improvement but not financially ruinous.

But when borrowers fail to even cover interest on their loans, their school should pay a much higher penalty—high enough to make college leadership question whether continuing to draw on federal student loans is worth it. Ideally, colleges will voluntarily withdraw their lowest-quality programs from federal loans and shift resources towards programs that are producing much better outcomes for students.

Require colleges to guarantee risk-sharing payments

One challenge in student loan risk-sharing is the time lag between when the government disburses loans and when it measures loan repayment outcomes. Ideally risk-sharing would encourage colleges to work on improving outcomes before the first penalty is assessed, but the long time lag weakens that incentive. Therefore, colleges who wish to participate in federal loans should put up a financial guarantee that risk-sharing penalties will in fact be paid.

Schools could satisfy this financial guarantee in multiple ways. First, the Department of Education could hold back a portion of student loan funding until outcomes are realized. If a college owes risk-sharing penalties, those will come straight from the undisbursed portion of the loan. Essentially, colleges will not get paid in full until they produce the outcomes that taxpayers expect for their investment in higher education.

Some schools will object that they need all their student loan funding upfront to provide high-quality education. If a college is confident that its programs will not result in risk-sharing penalties, it should have to convince a third-party financial institution of this fact. If a third party consents to guarantee any risk-sharing penalties the college may incur down the road, then the school may receive the full loan disbursement upfront. The third-party guarantee will safeguard taxpayers’ investment and provide some extra market discipline to support good outcomes at colleges.

Reward schools that offer high quality at low prices

The government should not simply punish bad outcomes at colleges; it should also reward schools that provide their students with upward mobility at affordable prices. To that end, policymakers should use the funds raised through risk-sharing penalties to increase federal Pell Grants for students in programs that charge modest tuition and deliver a reliable ticket to the middle class.

The federal government could selectively increase the maximum Pell Grant for programs where the ratio of median graduate earnings to tuition is high. This will encourage schools to enroll more students in high-value fields of study such as nursing and computer science. Moreover, phasing out the extra Pell Grant funding for institutions that charge high tuition will discourage schools from raising prices to capture the additional aid, as often happens now.

The Pell Grant program, which provides financial aid to low- and middle-income college students, is an ideal vehicle to deliver this outcomes-based funding. Institutions will only receive extra Pell Grant funding if they enroll more students who qualify for Pell Grants—namely, lower-income students.

Moving forward on accountability

Congress has a chance to reform the student loan program before runaway cancellation pushes it off the fiscal rails. The best path forward is to implement student loan risk-sharing, require colleges to guarantee that penalties will be paid, and use the revenue to boost Pell Grants for high-return programs. This will protect students from poor outcomes and reward colleges that serve their students well. But the clock is ticking: policymakers will need to act quickly in order to stop the next student loan crisis before it happens.