By Nazish Dholakia, Senior Writer, Vera Institute of Justice

In the decade that Luke White has been homeless, he’s received numerous tickets for simply existing in public spaces.

Vera Institute of Justice

“We’re just not welcome anywhere,” White told The Texas Tribune. “I can’t tell you how many tickets I have gotten . . . [for] sitting, lying, just the little stupid stuff I have on my record.”

White lives in Austin, Texas, where authorities have cleared several encampments in recent months following a public camping ban that voters reinstated this year. It mirrors a new Texas law that criminalizes public camping—and bans cities from adopting policies that prohibit or discourage the enforcement of any public camping ban.

People who don’t comply with the law can be ticketed, arrested, and fined up to $500. But Austin doesn’t have nearly enough housing or shelter space for the estimated 3,160 residents experiencing homelessness. Nevertheless, local authorities have forced unhoused people to disperse. Some have relocated to woods around Austin, where they are far removed from resources and services like food, health care, and sanitation.

The Texas law criminalizes people for trying to survive when there are no other options available—it does nothing to address homelessness. But Texas is not alone in adopting such measures.

Laws that bar people experiencing homelessness from sitting, sleeping, or resting in public spaces are prevalent across the country. Some laws prohibit people from living in vehicles. Other laws turn loitering, asking for money, and even sharing food with people into offenses punishable by fines or arrest. In many cities, public restrooms are not available overnight—or at all—yet cities prohibit public urination and defecation. All these policy choices discriminate against unhoused people as authorities eject them from public spaces; confiscate and destroy their property; and segregate them in often unsanitary and inhumane mass shelters and jails—practices that threaten their health and well-being and, ultimately, their lives.

We don’t know how many people experience homelessness in the United States, and all data sources have limitations. According to the National Center for Homeless Education, more than 1.3 million public school students experienced homelessness during the 2018–2019 school year. Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) most recent pre-pandemic survey counted 580,466 unhoused people on a single night in January 2020. That number—already considered an underestimate—has certainly increased. The economic fallout of the ongoing pandemic has forced more people to live without shelter, meaning homelessness could increase 49 percent over the next four years (it has been on the rise for the last five years).

Those experiencing homelessness are disproportionately people of color, the result of centuries of discrimination in housing, education, employment, health care, and the criminal legal system. Black people make up 12 percent of the U.S. population, but they account for 39 percent of people experiencing homelessness. Unhoused people of color are also more likely to be cited, searched, and have property taken than similarly situated white people.

The homelessness crisis is the affordable housing crisis. Untenable rent burdens have priced people out of their homes. Investments in affordable housing remain inadequate. For Priscilla Coughran’s family, as reported by NBC, a rent increase of $150 meant her family could no longer make ends meet. They were evicted and ended up living in their car. Domestic violence is also a leading cause of homelessness, particularly for women. And because of the multitude of barriers they face securing housing and employment, formerly incarcerated people are almost 10 times more likely to experience homelessness than the general population.

The crisis looms largest in California, where, instead of investing in permanent affordable housing and other necessary resources, local and state governments have deployed tactics to rid communities of the visible presence of unhoused people. An October 2021 ACLU report shows how local governments have harassed, cited, segregated, banished, confined, and incarcerated people who are homeless. Local governments have also withheld lifesaving public services from unhoused people and targeted the organizations trying to help them.

Chico, California, for example, proposed forcibly moving unhoused people to a patch of blacktop located hundreds of feet from an airport runway at the outskirts of the city, where temperatures routinely exceed 100 degrees. The “shelter” was essentially an open space with an umbrella, without water and power, miles away from food and other services. Those who refused to move would be fined or arrested. A court later rejected the proposal, but Chico continues to harass and displace unhoused people by carrying out sweeps during which authorities tow vehicles and destroy property.

When unhoused people set up camp in the parking lot of Santa Ana’s El Centro Cultural de México, leaders of the cultural center refused to evict them. So, the city started fining the cultural center, alleging trash and noise complaints. A few months later, the city executed a warrant and displaced the encampment.

In San Diego, one unhoused man was cited for spitting on a public sidewalk while brushing his teeth. The fine cost him more than $1,000.

The criminalization of homelessness is increasing as local governments find legal loopholes and replicate discriminatory policies, practices, and proposals from one place to the next. A National Homelessness Law Center (NHLC) report found a 92 percent increase in citywide bans on camping from 2006 to 2019. During that same time frame, citywide bans on sleeping in public increased 50 percent; on sitting and lying in public spaces by 78 percent; on loitering by 103 percent; and on living in vehicles by 213 percent. More cities are finding more ways to punish people experiencing homelessness.

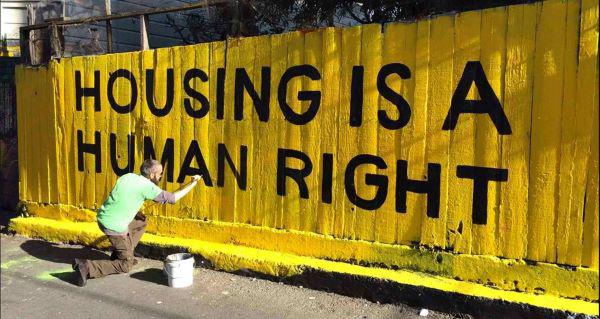

It doesn’t have to be this way. We can shift resources away from harassing, citing, fining, jailing, segregating, and displacing unhoused people and use those dollars to invest in real solutions, like Housing First approaches. The model is grounded in the idea that pairing people with permanent housing—without barriers or conditions—is the first step to ending their homelessness. Only after basic needs are met can they effectively pursue other goals, like securing a job or seeking treatment.

Housing First doesn’t mean “housing only.” Permanent supportive housing, a Housing First approach, combines affordable housing with access to voluntary support services, such as mental health counseling, substance use treatment, and education and employment opportunities. Rapid rehousing, another Housing First model, provides short-term rental assistance and services to help people get back on their feet quickly.

These approaches are cost-effective and make communities safer—unlike our widely accepted but misguided practice of criminalizing homelessness, which is the most expensive and least effective approach. Overcriminalization gives law enforcement free rein to exert authority arbitrarily and often violently. People experiencing homelessness are up to 11 times more likely to be arrested than those who are housed. This overcriminalization is costly. It fuels mass incarceration, compromises public health and public safety, drains taxpayer dollars, and causes grave suffering. Arresting and incarcerating unhoused people under laws that criminalize homelessness costs taxpayers $83,000 per person per year.

Our punitive approach toward people experiencing homelessness is detrimental and counterproductive. It only makes it harder for unhoused people to secure housing, find and maintain work, and access services. In attempting to “rid” communities of homelessness, governments wrongly prioritize the desires of the housed over the needs of the unhoused. Being homeless is not a crime, and we must invest in real solutions that create safe, stable, affordable housing for the millions in the U.S. who need it.

This is a content marketing post from Vera Institute of Justice, a Forbes EQ participant. Forbes brand contributors’ opinions are their own.