Leslie Fordham, Broward Cultural Division’s public artwork administrator since 2010, unintentionally honed her craft in a most uncommon approach.

“I sewed,” says Fordham. “I made dresses when I was a teenager and in my 20s, and I learned a whole lot about how sculpture goes together and how they make sculpture from those days when I did sewing. I made my own dresses because I liked going to a lot of parties.”

Early in Fordham’s profession, she labored with engineers and says that’s how the items got here collectively.

“What I don’t usually tell people: I worked then in the construction business and I learned how a barrel vault worked because it was pretty much the same as putting a sleeve in a dress,” she says. “There was a time I went and talked to architects, and they called my company and asked if I was an engineer because I seemed to know so much about how things work together.”

Additionally, Fordham “learned about planning and planning out a project.” These had been expertise, she says, she was capable of apply working in public artwork.

Fordham, 66, retired from her place with Broward County on Friday, Sept. 13.

She grew up in Washington, D.C., the place she says, “my parents were great art lovers. They took us to art museums.”

After visits to the Nationwide Gallery of Artwork, Fordham “came to love” the work of French Baroque artists Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain and of the 19th century impressionists.

She studied artwork and artwork historical past at St. Mary’s Faculty of Maryland and earned a Grasp of Arts in data administration at College of West London in the UK.

In August 2000, Fordham moved to Vail, Colorado, to run the city’s Artwork in Public Locations program.

“What I learned in Vail – and was able to apply here – is that it’s so important to ask people what they want, what they want to see. Let them know in advance what you’re planning. And those community outreach skills are essential,” says Fordham. “In a bigger community like this, the planning process is slightly different in that one needs to anticipate who’s going to have a stake in the public art, and think about who has questions, and be sure that you’re connecting with those folks in advance.”

After 9 years in Vail, Fordham accepted the job of public artwork supervisor in Lancaster, Pa. A 12 months later, she moved to Broward County and in August 2010 joined the cultural division because the county’s public artwork administrator.

“When I first came, there was still that bit of an economic downturn. There were questions about the future of our public art ordinance,” says Fordham.

She managed to deal with each the financial and political challenges.

“I learned so much about public art administration from having to react to situations outside of our control. Situations where the county was reconsidering how it wanted to do public art.”

Fordham says that was one thing she hadn’t anticipated going into the job.

“But I’d say that after the first two years, I was ready for just about any eventuality. I could handle it, I knew our codes inside out, the processes inside out, getting to know the commissioners.”

She recollects the machinations of the way it all labored.

“During the next five years, we were taking our public projects to our county commissioners in advance of them being approved, meeting with commissioners, meeting with the community. We were working on the county’s 100th anniversary [in 2015], doing a lot of murals and working very closely with Broward cities.”

CULTURAL DIVERSITY

Fordham says that along with Broward County being a bigger group than Vail or Lancaster, she was interested in South Florida’s cultural range.

“As I became more entrenched in the community here, we started looking at our public art collection and who the artists were who were making public art. And we knew that we wanted to reach out to artists who were more like our community, who better reflected the demographics of our community.”

Artist Addison Wolff, initially of Winter Park, Florida, moved to Broward in July 2020 after going to varsity and dealing in Indiana.

“The big move extremely pivoted my life from working retail. I was doing visuals at Saks Fifth Avenue, the department store up in Minneapolis,” says Wolff. “I was excited to come down to Florida. I knew the art scene in Miami with Art Basel was integral, and I was looking for a larger art ecosystem. And I had an affinity with Fort Lauderdale, and, especially, Wilton Manors.”

His artwork consists of sculptures, work, and inside design and is at present on show at Gasper Arts Heart in Dania Seashore, he says.

“Wolff’s practice explores queer identity, expression, and sexuality,” in line with the Gasper web site. “Themes of evolution, time, personal identity, societal influences, fluidity, and code switching are explored through non-objective compositions of broken color, collage, layering, erasure, and moiré effects, on canvas and hand built, ceramic forms.”

Wolff, who lives in Fort Lauderdale, acquired a nationally judged 2022 fellowship from the South Florida Cultural Consortium, which is a five-county initiative comprised of Broward, Martin County, Miami-Dade County, the Florida Keys and Palm Seashore County.

Broward Cultural additionally awarded Wolff a $10,000 2024 Artist Innovation Grant.

His 2024 ceramic sculpture “ochre/ruddy orange/midnight blues” will probably be displayed as a part of the Broward County Public Artwork & Design assortment.

“I want my art to be personal to me. As someone who is queer and young, it’s been a part of my life. It’s fundamental to kind of speak your truth and identity,” says Wolff, 36. “And I want to explore ways to express how I navigate life.”

Wolff says Fordham has performed a “fundamental” function in his improvement as an artist, “verifying that I’m a legitimate artist and verifying that my art has worth to the community.”

Fordham and others in her program “are really active partners in saying, ‘What do you need from us? How can we help you?’ Advancing you to make sure you stay in Broward, that you can work out here and don’t have to move on to Miami.”

‘WE OWE HER A LOT’

Phillip Dunlap, Broward Cultural Division’s director since 2019, says Fordham leaves a considerable legacy upon her retirement.

“We calculated 71 pieces of art that were commissioned during her tenure. That in and of itself, I think is a really big accomplishment,” says Dunlap. “Public art in Broward County is what it is in large part because of Leslie Fordham and her vision, her direction, and her leadership. We owe her a lot for that.”

Dunlap is at present reviewing functions to search out Fordham’s successor.

The Cultural Division is “expanding the concept or the idea of public art beyond our core program or the traditional public art program that commissions artists to do functionally integrated art, which is great and has a place,” says the 43-year-old cultural director.

“But with Leslie, we’ve been working on expanding that idea. We started an art purchase program where we’re purchasing art from Broward artists that will go in public spaces. That’s a new program. It’s not commissioned, but we’re actually purchasing art from artists. We’re looking at how artists can be change agents within county or municipal departments.”

Jacoub Reyes, 33, of Plantation, is such an artist.

Reyes’ “El Encuentro,” a brief video shadow puppet efficiency screened final 12 months on the Broward County Primary Library in Fort Lauderdale, was funded by the Artist Innovation Grant he acquired in 2023.

“For this project and this mode of art, it’s really based around accessibility. I wanted to talk about the history of the Caribbean and colonialism and its ripple effects that we see today, but in a very palpable way that any age or learning ability can understand or interact with,” says Reyes, whose mom is Puerto Rican and Cuban, and whose father is a Pakistani immigrant.

“What both of those have in common is colonialism,” explains Reyes. “The British came into India and separated Pakistan, Kashmir and India into three different states. And the same happened with Puerto Rico as far as . . . the colonial holdings from Spain and then, shortly after, the United States. Those are the overarching themes.”

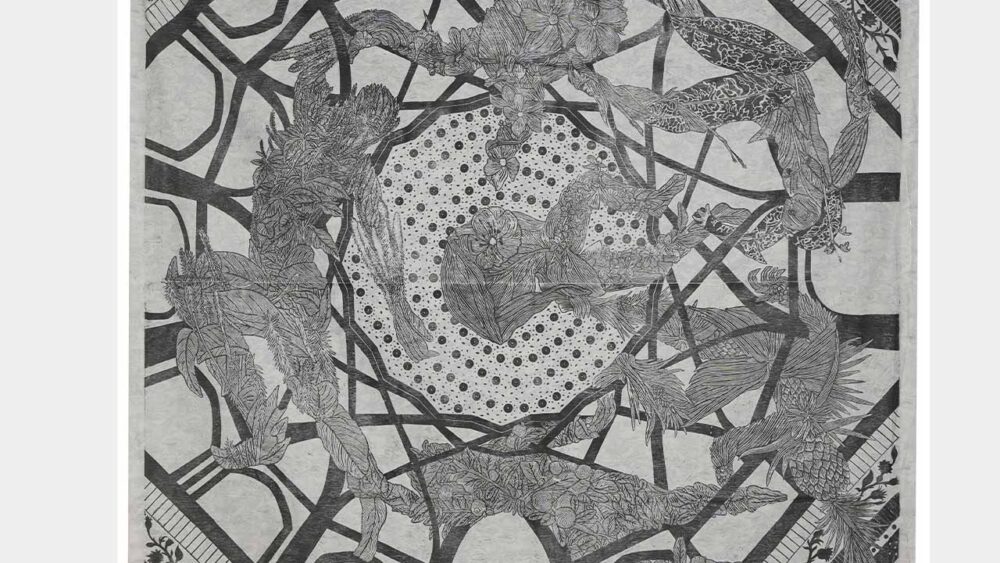

One other of Reyes’ works “made possible” by Broward Cultural assist: “Ornamental Figurations in Motion (Peace, Love, and Joy),” an 8-foot by 8-foot woodcut that depicts native and invasive species of vegetation present in South Florida and the Caribbean.

A CHAMPION AND MENTOR

Reyes grew up in New Brunswick, N.J., later lived in Central Florida and moved to Broward County about three years in the past. He describes Fordham as “an integral part of the Broward Cultural Division,” who has championed his artwork and turn out to be a cherished mentor to him.

“We usually have long conversations over the phone, or she comes to the studio and offers her experience, which has been totally valuable to me,” says Reyes. “All her stories and what she does and how she navigates public art and all those different facets. So she’s kind of been like a consultant, maybe the best way to describe it for me.”

Reyes says Fordham has made an influence in how he handles his artwork as a enterprise.

“She’s helped me navigate certain things in my art career that I might not be too versed in: the business side of the arts, negotiations, that type of stuff . . . She’s just been an arts resource on top of being an amazing person.”

Broward’s Public Artwork & Design program started in 1976, “with the vision of beautifying a rapidly-developing Broward County,” in line with a county web site.? “We administer an average of 80 art projects annually, including conservation projects.” There at present are greater than 310 public artworks on view all through Broward.

This system, which offers over $6 million in annual assist for cultural organizations and artists, now extends into municipalities all through Broward and Fordham has been on the middle of that growth.

“The other thing that we started, that Leslie was so great at, is to work with cities and help them create their own public art programs,” says Dunlap. “Leslie has led our public art teams in the creation of Dania Beach’s public art master plan. She’s currently finishing up the same with the city of Wilton Manors.”

Among the many spectacular public artworks commissioned throughout Fordham’s tenure:

- Alice Aycock’s white and blue “Exuberance” is displayed in a Port Everglades visitors circle outdoors Cruise Terminal 25, which is primarily utilized by Superstar Cruises (additionally identified for its white and blue colours). The sculpture, budgeted at $495,000, was accomplished in 2019.

- “Walking Sticks with Stories to Tell” (2019) by artist Claudia Fitch. The $220,000 sculptures are on show close to the African-American Analysis Library and Cultural Heart, 2650 Sistrunk Blvd., Fort Lauderdale.

- “Tidal School” by Mission One Studio, a $200,000 243-foot-long sculpture of painted aluminum and galvanized metal on grass plantings quickly to be accomplished at nineteenth Avenue and Eller Drive in Port Everglades.

- An in-the-works $6 million colour lighting mission for the E. Clay Shaw Jr. Bridge, also called the 17th Avenue Causeway bridge, which crosses the Intracoastal Waterway east of the Broward County Conference Heart. “That’s our biggest project yet,” says Fordham.

The general public artwork program is a mixture of visible and audio works, some apparent and others extra discreet.

Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood Worldwide Airport comprises examples of every.

“At our airport, we’ve got a couple of sound art pieces,” Fordham says. “You might hear bird noises. You might hear the sound of waves. You might hear a person’s voice saying, ‘You look beautiful today.’”

Fordham herself just lately was startled by certainly one of her personal acquisitions. “A couple of months ago, I had a 6 a.m. flight, and I was walking through a corridor where we had some sound art. I jumped, thinking, ‘Who was that who just said that to me?’”

Some artwork sounds are supposed to be extra nice than the standard noises heard in busy airports.

“If you’re standing waiting for your luggage, we have something called ‘musical warning beacons.’ Instead of just the usual sound you might hear to alert you that the conveyor belt is going to start moving, you have a musical warning rather than the glaring ‘beep, beep, beep.’”

‘FUNCTIONALLY INTEGRATED’

Public artwork shows are sometimes “functionally integrated,” she says, and typically so delicate they is likely to be missed as artwork, akin to designed terrazzo flooring on the Conference Heart and Broward property appraiser’s workplace.

“You’re not always going to stop and say, ‘Oh wow, that’s an amazing sculpture.’ You’re going to be walking across something that’s feeling pretty great and subliminally, potentially, you’re going to be feeling great because you’re not walking on the cracked sidewalk. You’re now walking on a lovely artist-designed floor that might be colorful, that might have text in it, imagery. Those are the kind of things that just make our lives richer.”

As her retirement approaches, Fordham ponders what’s subsequent.

“After the stress of the job is cleared a little bit and I can see the future coming, I really don’t want to divorce myself from the arts,” she says.

She’s pondering taking her expertise and placing them to make use of as an advisor, maybe.

“I’d like to explore the idea of advising others on their acquisition and purchase of art. I also care very much about public spaces and what art can do in the public space. If I can be involved in that – perhaps not in the municipal sense where I’m advising cities anymore – but advising other types of organizations that put art in public places, I would very much like to do that.”

She’s additionally trying ahead to only having the time to take pleasure in retirement.

“I have all the usual plans: traveling and playing. I’ve been learning French for the last four years, and I’m not finished learning that. I have some house renovations planned, as well,” says Fordham, who lives in Fort Lauderdale.

By the best way, she has no plans to renew stitching. “But I’m really interested in some Japanese embroidery and Japanese bags. Perhaps I’ll have time to do some of that when I retire.”

This story was produced by Broward Arts Journalism Alliance (BAJA), an unbiased journalism program of the Broward County Cultural Division. Go to ArtsCalendar.com for extra tales concerning the arts in South Florida.