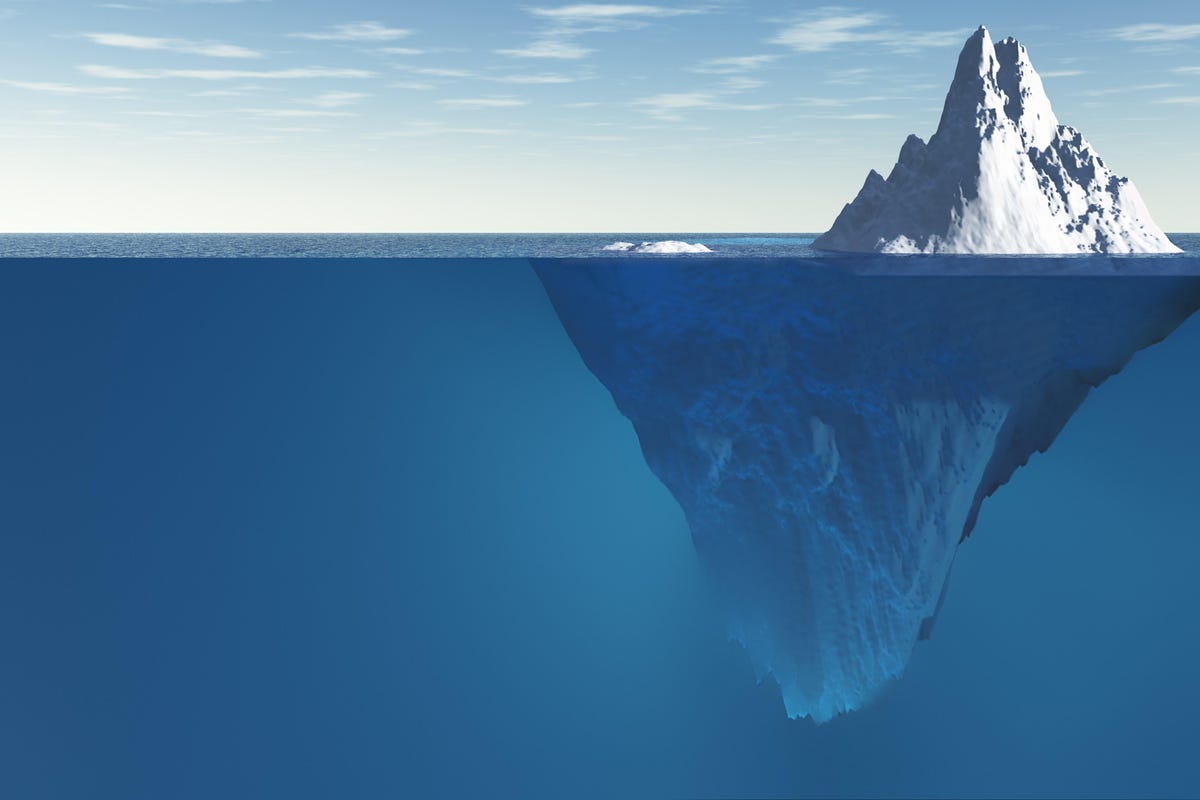

Hiding in plain sight

In November 2010, management guru Gary Hamel declared boldly in a Financial Times interview, “I am willing to stake my reputation that we will see more dramatic change in the way management is organized in the next 10 years than we’ve seen in the last 60 or 70.”

Almost exactly ten years later on November 14, 2021, the Financial Times management columnist, Andrew Hill, published his conclusion that the prediction had failed. No “dramatic change in the way management is organized” had materialized. According to Hill, “a manager from 2011, or 1991, or even, frankly, 1961” would still feel right at home in the office of 2021.

That conclusion is nonsense. Whether we realize it or not, we are already living in a new economic age—only the third in history, with radically different management practices that are driving the growth of the economy. The “digital age” is one name for the age, though there are others, such as “the information age”, “the age of platforms and ecosystems”, “the age of digital giants:, and “the age of disruption.”

The digital age has different economic dynamics, different management principles, different social consequences, and different political implications, as compared to the industrial era. The industrial-era economy hasn’t disappeared, but it is relatively less valuable and important.

The Radical New Management Innovation

The new management innovation are very different. Instead of an industrial-era focus on internal efficiency and outputs, the primary preoccupation in the new age is external: an obsession with creating value and outcomes for customers and users. Instead of starting from what the firm can produce that might be sold to customers, digital firms work backwards from what customers need and then figure out how that might be delivered in a sustainable way. Instead of limiting themselves to what the firm itself can provide, the firm often mobilizes other firms to help meet user needs. Instead of leadership located solely at the top of the organization, leadership and initiative that create fresh value are nurtured throughout the organization. Instead of tight control of individuals reporting to bosses, self-organizing teams throughout the firm create value by working in short cycles and drawing on their own talents and imagination. Instead of the steep hierarchies of authority of industrial era-firms, digital firms tend to be organized in horizontal networks of competence. In these ways, most of the central management tenets of the industrial era have been upended.

MORE FOR YOU

Far from feeling right at home, the “managers from 2011” are spending frantic days and sleepless nights in 2021 trying to understand the puzzling new volatile, uncertain, complex ambiguous (VUCA) world of 2021, in which they find themselves. They are grappling with a world in which disruption can come from non-competitors, and put established firms out of business almost overnight, a world where firms with no physical assets can crush firms with massive physical assets. Even the least observant “managers from 2011” are aware that their firms are heading for a meeting with the Grim Reaper if they continue as they are and are desperately flailing at “digital transformations” which are mostly failing.

The fact is that Hamel’s “radical management changes” are staring us in the face. They are obvious not only in the five largest companies with a combined market capitalization of some $10 trillion—equivalent to almost half of the U.S. GDP, but also in smaller digital winners that are growing fast, including AirBnB, AMD, DoorDash, Etsy, John Deere, NVIDIA, Shopify, Spotify, and Zoom.

It is not just technology that is responsible for these changes: it is the combination of exponential technology and new management innovation models.

These different management models can quickly attain global reach within a few years. In the industrial era, such growth and scope had usually taken decades. Now global scale—and the firm being the best in the world at what it does—are becoming mandatory. In the new age, radically different business models become possible and even necessary: from markets to platforms and ecosystems; from ownership to access, from workers to co-creators of value, from sellers and buyers to providers and users.

That the management changes are real and massive in scale is obvious from their impact in our lives. To most people, they are like magic. Very quickly, the digital economy has transformed how we work, how we communicate, how we get about, how we shop, how we play and watch games, how we deliver health care and education, how we raise our children, how we entertain ourselves, how we read, how we listen to music, how we watch theater and movies, how we worship; in short, how we live. The transition was accelerated by the pandemic of 2020-2021.

It is true that many big old firms are unsuccessful in the new age and are suffering dire financial consequences for the failure, only alleviated by financial engineering gadgets, like share buybacks, M&A, favorable regulations and so on.

Curiously, economists and journalists are still mainly looking for management innovation in the wrong place—in the icons of yesteryear, such as Nucor, Vinci, Svenska Handelsbanken, Michelin, 3M, and IBM— firms which are pursuing modest changes at the margin but are still largely stuck in the industrial era mindset. As a result, they are performing worse than the average firm in the S&P500.

Such economists and journalists are still viewing the world through industrial-era glasses and largely ignoring the digital economy, even though it is now almost half of the overall economy and growing much faster than these older firms. Such firms are now treated by the stock market as cash cows to help fund the firms that are on genuine growth paths.

It is true that when economists and journalists focus on these old industrial firms, making partial changes at the margin, it can seem that nothing much has happened as the new world doesn’t fit their equations and models that are based on a marketplace of physical products. Sadly, they too are destined to be disrupted as surely as the firms still living in the industrial era that they are studying.

Given the management innovation under way, Gary Hamel’s prediction has been proven and his reputation remains safe. It’s just that the Financial Times is looking for it in the wrong place.

And read also: