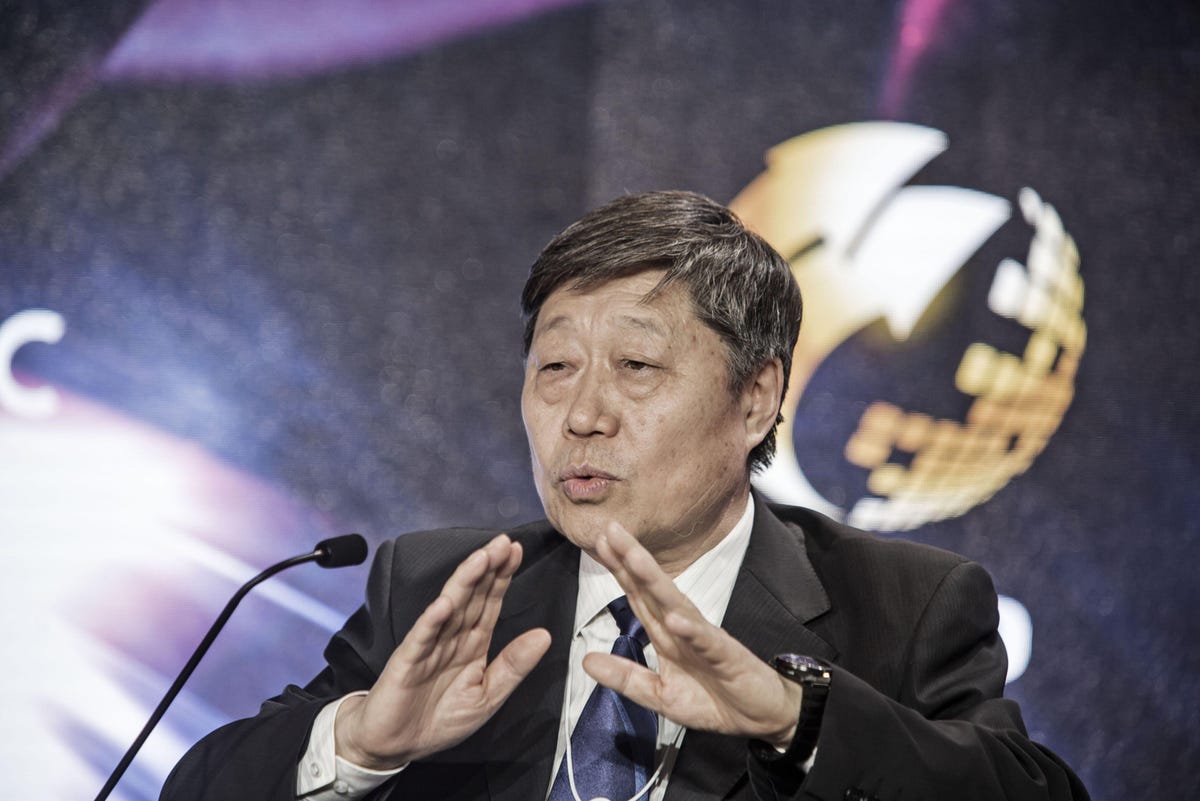

Zhang Ruimin, chairman and chief executive officer of Haier Group, speaks during the World Economic … [+]

The decision this morning by Mr. Zhang Ruimin, Chairman and CEO of the Haier Group, to not participate in the nomination of new directors, has taken many of his admirers by surprise. The long-serving architect of Haier’s Rendanheyi approach to organizational transformation will transition to Honorary Chairman, and will be suceeded by Mr. Zhou Yunjie as Chairman and CEO, with Mr. Liang Haishan as President. Despite this succession having been thought through quite a while ago, and with both Zhou and Liang presently effectively serving in these roles, there are, nonetheless, already early signs of concern among busness observers regarding Haier’s future direction. This is not unusual; every executive succession in iconic firms is greeted with cautious anticipation, no matter where in the world they take place.

Well before great leaders leave their positions, we begin wondering what we will do without them. Haier’s Zhang Ruimin is no exception. For the past two decades, there have been recurring questions as to how the organization will fare, once he steps down? Mr. Zhang has been aware of these speculations, and he has occasionally referred to the concerns associated with leadership transitions at Apple, Dell, Microsoft and General Electric. Yet, in the case of Haier, Mr. Zhang has been puzzled why it would be included with these others. Unlike so many organizations, where it is felt that a worthy successor may not be found, when it is Zhang’s time to depart from Haier, he will be leaving an organization that is not leaderless, but, leaderful.

Early in the twenty-first century, Mr. Zhang recognized that the pace of change, and the growing complexity of the customer experience, required more leadership, not less; but that that leadership needed to be redistributed lower and broader throughout the Haier community. His response was to once-again rethink the organization that had been born in the nineteen-eighties as the Qingdao Refrigerator Company, and which had continuously been reinvented over nearly four decades, in order to create more market views, more ideas about the future and more leadership opportunities. Out of this came more ideas, rather than fewer, ideas such as microenterprises, platforms and ecosystems. These went beyond mere organizational redesign, and represented a heroic recasting of the leadership role, fundamentally expanding autonomy not only within the organization, but also blurring organizational boundaries with ecosystem stakeholders, so that our views of business organizations would never look the same again; where relationships have become more important than assets, and where customer experience shapes every activity involved in creating and sharing value.

There is considerable irony that such a fertile leadership imagination could originate with someone who had begun his career as a government official and had only moved into a real market-driven leadership position when no one else could be found to direct an organization that many regarded as hopeless, the Qingdao Refrigerator Company. Mr. Zhang emerged from this early experience respected as a visionary leader, and Qingdao Refrigerator was reborn as Haier. These successes were not easy, nor magic. Mr. Zhang regarded organizational transformation as a continuous endeavor, not episodic, and the result of a combination of big dreams (daring business models) and small details (mastering the granular choices needed to forge a supportive organizational culture). For four decades, he continuously experimented, always in pursuit of the same few guiding principles: a great customer experience, the value of entrepreneurial energy, and sharing the value-created amongst those who created the value to be shared.

Throughout Haier’s transformation journey, in the spirit of Peter Drucker’s call to every employee to think of themselves as a CEO, Zhang Ruimin has consistently reconfigured Haier so that almost every employee really can think of themselves as a CEO, and act accordingly; what he discovered was that when employees were granted an unusual amount of autonomy, they eagerly accepted it. In the process, the basic unit of work at Haier became smaller and smaller, to the point where, today, it is truly a micro-enterprise. Kevin Nolan, of Haier’s General Electric Appliances, has observed that his job, as CEO at GEA, is to make organizational units even smaller, which results in a need for more leaders.

MORE FOR YOU

More leaders? Does that sound like a good idea?

Remember, we are talking about more leaders, not more managers. Mr. Zhang has observed that “we are entering the era of the loss of managerial control,” and part of what he is referring to is that as employees leave behind their traditional role as order-takers, and, instead take on responsibility for their own fates in a market system, the whole argument for managerial control erodes, and is replaced by the entrepreneurial dreams of each employee. This outcome promises to foster greater energy and engagement, more and more novel ideas, and a higher probability of talent fulfillment. The organization is no longer a prison for employees’ souls, but a vehicle to launch their dreams.

Haier’s daring in rethinking the organization, and its success in building a global market-leading firm, did not go unnoticed by the business press and academic observers. Harvard Business School’s first Haier case was written in 1998, and, by 2015, HBS had added 16 more; today the total stands at 27, not to mention cases written by other schools including IMD, IESE and Wharton. In 2011, Fortune magazine called Zhang Ruimin, a “new management icon,” and suggested that “You’d be hard pressed to find a manager who is more innovative or fearless than the head of Chinese appliance giant Haier Group.” In 2012, when Fortune magazine chose its “executive dream team,” featuring the likes of Intuit’s Bill Campbell, Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, Zhang Ruimin was their number one selection

Thinkers50 ranked Mr. Zhang fifteenth in their 2019 ranking of management thinkers, having made the list three years on a row.

In many ways, Mr. Zhang’s leadership legacy is often expressed by the metaphor of a startup; small, autonomous teams and frenetic entreprenurial energies. Mr. Zhang however, suggests that it is not so much Haier which is the startup, although there are many startups within Haier. Instead, Haier is an accelerator for many startups. It has become a platform that helps people try, and hopefully succeed, with their ideas, and make faster scalable learning, resulting from all of these efforts, a reality. In a world becoming increasingly unfamiliar, because of the convergence of technology and personalized, ever-more-complex customer expectations, Mr. Zhang expects that Haier will wind-up in the right place, at the right time, not because it can better predict the unpredictable, but because it has achieved greater access to different expertise domains and, as a result, has placed more informed bets than anyone else. He has the strong belief that it’s likely that a few of these bets will turn out to be market winners. Such an approach requires more leadership, largely located in autonomous microenterprises, rather than building bureaucratic pyramids, where managers are neither leaders, nor close to the action. The fact that he has designed Haier to be a boundaryless learning organization, hosting a portfolio of opportunities, but where the market directly makes the key decisions that determine which projects win or lose, and which teams succeed or fail, undoubtedly shifts the odds in Haier’s favor. Corporate strategy, to the extent that it exists at all, is now being forged on the front-lines of customer engagement, rather than remaining the province of priviledged staffers, looking down from a distant corporate headquarters.

It is the leaderful organization model, where every employee can envision themselves as a real leader, that generates abundant energy, insights, novelty and achieves higher talent fulfillment. Unlike traditional organizations, where management all too often enervates the workforce, and slows things down, Mr. Zhang’s experiments have shown that complex organizations can be engines of economic and personal growth, and where succession should not be an issue, because it is happening everywhere, all of the time, as a natural phenomenon.

So, what sort of person leaves a legacy such as this; no managers, yet many leaders? What can we learn from Mr. Zhang himself? Many stories have appeared over the years, trying to capture the essence of Zhang Ruimin’s leadership style. The one leadership trait that seems to consistently appear in each story is his curiosity; Mr. Zhang is the quintessential curious leader. Not surprisingly, he is particularly interested in what could be done differently in order to provide a better customer experience, and/or to unleash entrepreneurial energies within a complex organization. A visit to Zhang Ruimin’s office is similar to a PhD defense. No matter what managerial topic is on the table, it seems as if Mr. Zhang has read more, knows more and is personally familiar with the authors of the ideas being discussed. What Mr. Zhang sees, given the perishability of knowledge, is that learning is more important than knowing, and he has accordingly interpreted his role as CEO, and then as Chairman, to be an exemplar of active learning, and experimentation. Today’s Haier organization is built on that same model. It is an organization which is closer to the customer (zero-distance), in order to learn more, faster; and, it is quicker to execute because of the barriers which hinder speed of execution have been removed, and the trust that it places in its employees grows out of their own entrepreneurial confidence. Haier is well positioned to make spontaneity a competitive advantage as a result of the ecosystem behavior it supports.

Zhang Ruimin’s legacy, therefore, is inherently outside-in. It emphasizes awareness, learning and partnering, all in the service of better customer experiences. Leadership, after all, is about successfully directing people in the face of external vagaries, and that is why more real leaders are necessary, to learn, to engage with customers and partners, and experiment; to move the organization forward, and out of the familiar. Management, on the other hand, is inherently inside-out, it distracts us from the customer experience mission, and asks us, instead, to focus on our own organization, its structure, measures and rewards; that is why, fewer managers are preferable. In a very real sense, Zhang Ruimin has been practicing the lessons of his own leadership legacy for quite a while, and they are displayed each time that Haier transforms itself.

________________

I first visited Haier in 1997, as the Executive President of CEIBS, and have remained in close touch with Zhang Ruimin since then. After writing several cases about Haier, in 2013, I co-authored “Reinventing Giants,” which examines Haier’s multi-decade transformation journey. Since then, I have continued to write about Haier and for the past two years have had a consulting relationship with Haier, relating to better understanding the logic and dynamics of Rendanheyi. It has been a priviledge to watch this ongoing transformation journey and I wanted to share what I think has been a unique vantage point for viewing the leadership story involved.