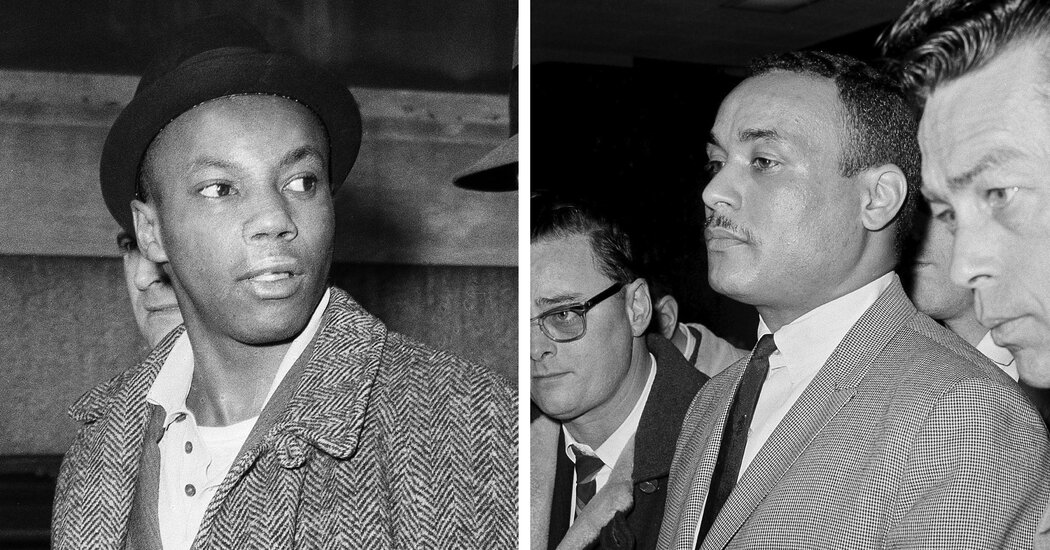

At the trial in 1966, prosecutors cast Mr. Islam, who was once Malcolm X’s driver, as the assassin who fired the fatal shotgun blast. Mr. Halim and Mr. Aziz were said to have followed close behind, firing their pistols. Ten eyewitnesses said they had seen Mr. Islam, Mr. Aziz or both.

But the witness statements were contradictory, and no physical evidence tied Mr. Aziz or Mr. Islam to the murder, or even the crime scene. Both men offered credible alibis, which were backed by testimony from their spouses, friends and others.

And when Mr. Halim took the stand for the second time during the trial and confessed, he insisted that his two co-defendants were innocent.

On March 11, 1966, all three defendants were found guilty and, a month later, sentenced to life in prison.

Even then, evidence was already pointing to another theory of the case.

Mr. Stevenson, who has spent much of his career fighting against wrongful convictions, said the assassination of Malcolm X, followed three years later by that of Martin Luther King Jr., traumatized Black people in the 1960s, but finding the truth never seemed to be a priority for law enforcement and the government.

Wednesday’s acknowledgment, he said, “just underlines how casually and recklessly these cases were investigated and ultimately concluded.”

“It undermines already tenuous and fragile confidence in the rule of law to protect Black voices that were challenging bigotry and discrimination,” said Mr. Stevenson. “And it also just represented our continuing problem with reliability and fairness, and those are the problems that we’re still reckoning with today.”